Last weekend, the Biden administration took the momentous step of allowing Ukraine to use the American long-range missile system known as ATACMS to strike deep within the Russian territory of Kursk, just months before Donald Trump is set to move into the White House.

Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelinsky expressed his support for the move. “The rockets will speak for themselves,” he announced. The Kremlin responded with a swift denunciation, saying Biden’s decision would lead to “a new round of tension.”

Until now, the UK and France have been supplying Ukraine with long-range missiles, with the caveat that they not be used to strike inside Russia. The U.S administration said the policy change was due in part to North Korea’s recent decision to deploy 50,000 of its troops to fight alongside Russia.

For the past two years, Catherine Philp, one of Britain’s foremost foreign correspondents, has covered the ebbs and flows of the war in Ukraine for The Times of London. This week, I’m thrilled to have her on The Reporters to discuss a trip she took inside Ukrainian-controlled Russian territory in August, 2024 which resulted in her story Inside Occupied Russia, Where the Reality of the War Has Come Home. Below are some highlights from our interview.

Can you tell us a little bit about your relationship to the broader Ukraine story? When did you start covering it?

I first went to Ukraine just before the invasion in anticipation that it would happen, or that, nonetheless, there was a huge story there, whatever transpired.

As it became apparent the Russians were going to invade, I stayed in Kyiv, which became the centerpiece of the story because the Russians immediately started moving on Kyiv. It was a very intense and immediate way to experience Ukraine from the get-go.

In the beginning, Russia made a forceful advance; then Ukraine made a bit of a comeback, only for Russia to regain the upper hand. Now, in the last few weeks, there’s been another minor reversal. Could you set the scene for us? Where does this story take place, and what is the significance of this particular dateline (for people who aren’t familiar with the term, dateline refers to where the story is reported from)?

This story is about a trip I took to Ukraine in August, which was long-planned as part of our regular coverage. The timing was interesting, as Ukraine was facing substantial losses in Donbas, with Russians advancing. President Zelensky made an audacious decision to invade Russia at a point far from the front line, in the north of Sumy Oblast.

Most Russian troops were concentrated in Donbas, so the border in this area was lightly defended. The Ukrainians opened a completely new front by crossing into Kursk, a region in Russia. A junior colleague had been in Sumy and talked to soldiers, but we hadn’t yet decided whether to try to enter the area the Ukrainians had taken.

When I arrived, I immediately asked my editors in London about their stance on it. We follow strict security protocols; decisions like this are no longer left to reporters on the ground. We’d also withdrawn our Moscow team early in the war because Russia had implemented a law threatening imprisonment for reporting on the war or even calling it a “war” rather than a “special military operation.”

There was another complicating factor: our sister organization, the Wall Street Journal, had a reporter, Evan Gershkovitz, who had recently been taken prisoner by the Russians, presumably as leverage for a prisoner swap. [Gershkovitz was released in early August as part of a major prisoner swap.]

In addition, crossing into Russian territory would mean facing the new front line in the Ukraine war, so it was a significant risk. This part of the decision was partly mine to make, based on my own risk tolerance and whether my team members would be comfortable with it. But first, I needed to get approval and set the decision-making chain in motion in London. So on my first day in Ukraine, I set all these balls rolling, headed to Sumy, and crossed my fingers.

Take us into the story. Can you read the first paragraph?

The story is datelined Suja, the main town in Russia's Kursk region and the primary population center the Ukrainians took when they entered.

Galina had never given her country's assault on Ukraine a second thought until it roared back across the border to her front door. “I didn't think about the war at all,” she said. “It was happening miles away in a different country. What did it have to do with us?” Plenty, she discovered in the morning she woke up at home in Suja to the sound of shelling, explosions and gunfire as thousands of Ukrainian soldiers stormed across the border into Russia.

Let’s talk about safety for a second. From your editor’s perspective, what was that conversation like? I remember one of my frustrations in similar situations was the way editors would say, “You’re the one on the ground; you ultimately have to make the decision. Do you feel safe?”

Of course, there’s an internal battle—wanting to go and get the story, knowing they want you to, but also understanding they’re covering themselves, even though they genuinely care about your safety. So what were they saying, and how did you land on the decision to go?

Interestingly, while my views were considered, it wasn't simply a matter of saying, "you on the ground know what to do." There was a legalistic dimension to this story. The concern was about Russia's potential legal retribution if I crossed into the country illegally. Of course, I had to be comfortable with the risk, and the only way to go in was with the Ukrainian military, traveling in an armored vehicle with them. But the question remained: how would the Russians treat me if I were captured?

Different people had varying opinions on this, especially given the case of Gershkovich. That situation was traumatic and involved complex negotiations for his release. This scenario was unusual; typically, risk assessments focus on personal safety. In this case, there were broader implications. Other journalists I knew decided against crossing the border because their organizations still had staff in Moscow, but since we no longer had anyone there, that wasn't a consideration for us.

Tell us about the trip. What happened as you moved through Ukraine and headed east into Russia, essentially behind enemy lines?

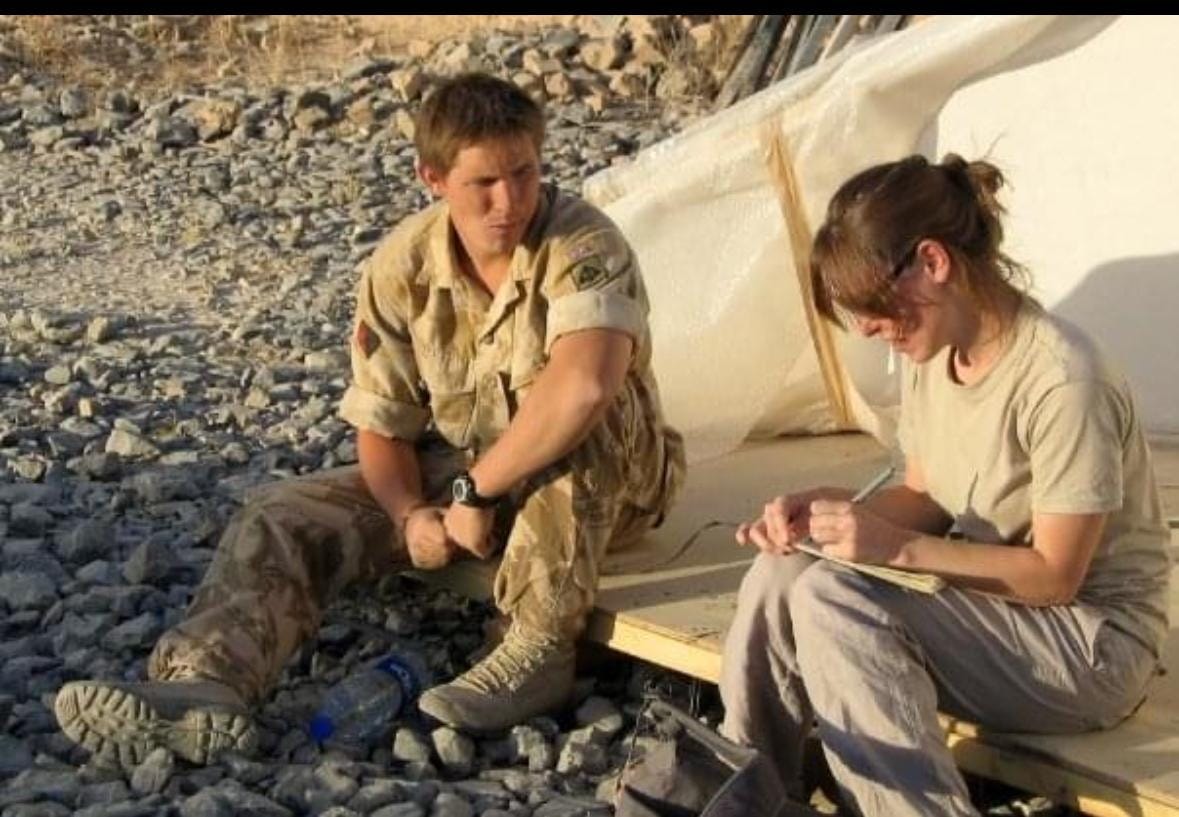

In a convoy on the way to Kursk, Russia, 2024.

It was challenging to gain traction with the Ukrainian army unless you were willing to cross the border, so we had to navigate around that. We talked to soldiers who had participated in operations by visiting the local hospital, where lightly wounded soldiers would often come outside to smoke. Fortunately, many people in Ukraine smoke, especially soldiers, which allowed us access to them in a situation where we otherwise wouldn’t have been allowed.

Initially, the soldiers told us the operation was easy compared to Donbas, saying they essentially walked in with no resistance. However, the day before we were set to go, we received a different account from the soldiers we spoke with. They mentioned that the Russians were starting to resist and that some units had suffered heavy losses, indicating the first real pushback from the Russians.

When we asked them about the situation in Crimea, one soldier warned us, “Don’t go; it’s hell in there.” This comment particularly spooked my translator, who had previously joked about wanting to join some irregular soldiers on incursions into Russia. That evening, she texted me saying we had permission to go, but she preferred that our driver, Losha, accompany me instead. Luckily, Losha spoke both English and Russian, which was crucial given the language differences.

The next morning, we met with the Ukrainian army and boarded an armored vehicle. Before crossing the border, we passed a field on fire, a grim reminder of the conflict we were entering. Ukrainian soldiers had warned us about glide bombs, an updated Soviet munition that was highly lethal and difficult to defend against. As we crossed into Russia, we saw massive destruction around the border posts, evidence of previous fighting.

Once we arrived in Suja, the first thing the Ukrainians told us was to watch out for FPVs, or first-person view drones, which are used for surveillance on the battlefield. I had previously witnessed how these drones could observe people going about their daily lives without them knowing. It was chillingly intimate what they could see. So when someone tells you to watch out for those drones, you suddenly realize that somewhere, someone who wishes you harm is watching you in that very same way and should they wish to disrupt our visit, they could do so.

We've covered conflicts for many, many years, and just listening to you talk about the drones makes me wonder how this conflict differed from, say, Afghanistan or Iraq. I would imagine that would be one of the ways, but are there others?

There are ways in which it’s different, and I became acutely conscious of this in the very early days, essentially when the Russians first invaded Ukraine. I realized that I hadn’t really been on the pointy end, kind of at the mercy of a fully armed conventional war by a state actor. If you think of somewhere like Afghanistan, we could have been hurt by our own side, by the Americans or NATO. Same in Iraq, but we certainly weren’t the target, nor were we necessarily with the people who were the target.

Catherine in Helmand Province, Afghanistan, 2008.

Suddenly, I remember getting up in the morning to do a radio spot with Times Radio, and they asked, “What’s it like being at the end of a 14-mile armored convoy of tanks coming down?” I dissembled a bit because I didn’t know I was at the end. After I got off, I switched on CNN, and sure enough, there were aerial pictures of this miles-long armored convoy. It was very unsettling, and I realized I hadn’t really been in a conflict like that before.

This is highly unusual, much more of a TV thing, but we had security—high-risk advisors with us, many of whom were veterans of Afghanistan and Iraq. It became very apparent to me that they hadn’t been on the receiving end of a conflict like this either. They were very unsettled when we went into situations where we were at risk of artillery fire, for example, because they had been dealing with insurgencies. They hadn’t been at the other end of people firing artillery at them or airdropped bombs.

In Kyiv, we actually witnessed fighter jets having aerial battles. That’s not something I think I’ve really seen before.

Being a reporter on the ground in essentially a kind of World War II-style conflict in Europe, no less, must have been deeply new and incredibly destabilizing, even for someone like you who has been doing this for decades.

I will say that the one factor we didn't have to deal with, which I was grateful for—you and I have reported in places where we are not seen as journalists but as representatives of the West. We’ve been in places with jihadist activity, and that is possibly our main fear—being taken hostage or, you know, not just killed in combat, but actually hunted down by people.

Although I would not have wished to fall into Russian hands, which would have been a bad thing, I was aware of that and knew it should not happen. However, I never felt hunted in the way that I think I did in some of the post-9/11 conflicts in the Middle East. So, that was a refreshing change. I would take the danger of shellfire over the feeling of being hunted any day.

None of this complexity and nuance that we've been discussing made it into the story, rightly so, because it underscores just how fraught so much of the thinking is. It highlights how difficult and complex the decisions are when you're dealing with a situation like this, where you've got multiple actors—and state actors in this case—along with immense security challenges. You have to figure out how to balance all that. One thing I am curious about is when you were talking about the drones—how has technology generally changed both the conflicts that you're covering and the way that you report on them, as well as your understanding of these conflicts?

A lot of that information is now available on social media, where discussions about the situation take place. Of course, this comes with the usual challenges of verifying that information. We live in an age of information, disinformation, and misinformation, and sorting that out is crucial.

You want to conduct thorough research and gather as much insight as possible, but you also need to stay open to what you experience on the ground because that’s at the heart of what we do—there's no substitute for it.

That said, I never would have seen the territory I was about to enter through a drone camera feed, provided by one of the participating militaries, days before going there. That was quite odd.

So you’re in this vehicle with the Ukrainians, you crossed the border, now you're in Russia. First impressions?

It doesn’t look very different. That part of the world looks pretty similar. It was once the Soviet Union, so this border has only existed since Ukraine’s independence.

How far are you, by the way, across the border?

It’s about six miles. When we got out in Suja, it was striking that there wasn’t an enormous amount of damage. The only damaged building in the center of Suja was the city administration, which had seen some fighting. There was a statue of Lenin in the square, which you obviously don’t see in Ukraine, although they have popped up in areas where the Russians have taken Ukrainian territory. Lenin had been partially smashed, and a Ukrainian flag had been hoisted over him. There was also graffiti in the square that could be seen from above, which read, “Russians teach your soldiers how to fight. There are thousands of them rotting in the fields.” That was clearly a bit of info propaganda from the Ukrainians.

“I never felt hunted in the way that I think I did in some of the post-9/11 conflicts in the Middle East.”

The real difference came when we met Russian civilians there. The Russians had been taken by surprise in this assault and hadn’t made any official effort to evacuate, so people inevitably got left behind. It would be unfair to say they were completely representative of the population, as they tended to be those without the means to leave—often older individuals or those who were disabled or struggling with alcoholism. I also met a medic who stayed behind because he felt it was his duty.

What struck me was that the people we met had a very different mentality compared to the Ukrainians. There was a sense of passivity and disengagement. When I read the beginning of the story, I mentioned Galina, who didn’t care about the war. It wasn’t just that she thought it didn’t affect her; she simply didn’t care about it at all. That was extraordinary to me, especially when in Ukraine, it’s impossible to meet anyone whose life hasn’t been changed by the war. Just a few miles across the border, it had zero impact on their lives, and it just wasn’t something that engaged their daily thinking at all.

Now we're seeing Russians from a completely different perspective. They are the ones who have been displaced, seeking shelter, food, and respite from the war. This has not been your beat until now; you've been on the Ukrainian side. One thing I was interested in exploring is this idea about the Russians being forced to reconsider their own views of the war. It seems that this became immediately apparent to you.

I mean, that was really my biggest reason for wanting to go. I thought this was an extraordinary opportunity to speak to those people. I was conscious of the fact that you always have to consider the situation when you come into this scenario with an enemy army. So, a lot of my conversations were conducted out of earshot of Ukrainian forces to avoid influencing what was said.

Some of the conversations we had were interesting because the Ukrainian forces were present as well. For example, one woman had come from the Donbas, a region in Eastern Ukraine where the Russians have backed a local insurgency and essentially fermented a separatist movement. She criticized the Ukrainians, saying they had shelled civilians in the Donbas, which is a narrative often pushed by Russia. However, she was from the Donbas herself, so she had experienced it firsthand. She expressed concern about whether the Ukrainians would harm her for speaking out.

Two weeks after much of the fighting, it was striking that many people were still in shock. They lived in such proximity to the war but did not expect it to have any consequences for them. While there was some nuance in what people said, there was a clear discontent toward Russian authorities for not helping or arranging evacuations.

The most extraordinary moment for me in confronting the narrative the Russian civilians had been fed about the war was when the Ukrainian forces showed them images and videos of the destruction in Ukraine. This was clearly a deliberate effort on their part. Interestingly, some of the footage was rather tame; they weren’t showing the worst of what had happened in places like Bucha. However, as they watched this video of a village, a civilian military liaison propped up a laptop and showed them footage of Russian speakers in Ukraine discussing the destruction of their communities.

This was significant because the narrative Russians have been fed is that the special military operation, as Putin calls it, is meant to protect Russian speakers who are being violently persecuted by Ukrainians. By highlighting Russian speakers in the video, the Ukrainians aimed to undermine this narrative. For some viewers, this was enlightening, while others found it challenging to accept.

“It was chillingly intimate what they could see.”

For instance, the mayor of a small village engaged in civil discourse with the Ukrainian forces, who were making an effort to show that they were different from the Russian forces that had invaded Ukraine. They were providing supplies, food, water, and medication to the Russians, almost as if to say, "Look how different we are; we take care of the people." Interestingly, no one seemed afraid of them.

However, accepting this alternative version of events was difficult for some. The mayor repeatedly turned to me, not the soldier, to point out that similar things had happened in Belgorod—that their buildings had been hit by Ukrainians too. She tried to draw a parallel, even pointing to a broken window in the building where we stood, as if that was comparable to the destruction in the video.

It wasn’t until the video showed footage of mass graves being disinterred in Bucha that she conceded there was a difference. I pointed to the screen and asked, "Are you saying you have mass graves in Belgorod too?" She admitted that such atrocities had not occurred in Russia.

I sensed that some of the people you spoke to wanted to say more but weren't sure if they should or could. Others, like the mayor, were much more strident in their denialism or willful ignorance.

You had this great line that I wrote down: the mayor pleaded ignorance. “The war had nothing to do with them, she insisted, and accordingly, they had not learned anything about it.” When I read that, I thought she had been very well trained by the Russia she has lived in all her life to navigate these informational minefields.

As a reporter, it's fascinating because you constantly have to deal with that. Someone might say something that contains a nugget of truth, and you need to find a way to tease it out. In these circumstances, it must be particularly difficult, right? You have soldiers watching you, and the people you’re speaking with are also watching the soldiers, trying to figure out where you stand. How do you navigate that as a reporter?

There's always a challenge when people tell you things that are blatant untruths, and you have to navigate how to quote them when they're stating something false. Sometimes that British understatement helps us because you can just write down what they said and let it take on its own life. I have no idea if the Ukrainians shelled their power station, as she claimed. I included it in the context of everything else she was saying.

She was the only person who flat-out refused to let me use her name, so she exists in the story simply as "the mayor." I thought that worked well because she acted as an official mouthpiece. She insisted she didn’t watch television news, and many narratives from people in Russia come from their limited information streams, both by their own choosing and due to state propaganda and media control.

“I've had more interference from the British military in different places than I ever have from the Ukrainians.”

I found it hard to believe, as some of her statements clearly couldn’t have come from her own experiences and could only have originated from those sources. The Ukrainian soldiers didn’t try to insert themselves into my reporting process at all. Their interactions in bringing the video to show these villagers were irresistible because they revealed so much about the information world they inhabit and their views on the war.

When I spoke to people, the soldiers didn’t interfere, which made it a trusting environment for reporters. Ukrainians, both civilians and military, seem to understand our job and recognize the tangible benefits of telling their story about what the Russians have done in Ukraine. They rarely attempt to manipulate you. In fact, I've had more interference from the British military in different places than I ever have from the Ukrainians.

The Ukrainians have just a few ground rules, primarily about not giving away strategic information. For example, while I was with a drone team, I thought they might have issues with me showing what was on the screen, but they didn’t want me to use photographs of the drone itself, as it could provide useful information to the Russians about targeting. They asked me to blur that out. Overall, they don’t interfere much, and they didn’t on that trip, so it wasn’t difficult to have conversations away from them.

This brings us to the real drama of your trip, which stems from the Russians' very different attitude toward information, reporters, and journalism. Can you tell us what happened with the Russian government during or after your trip?

It was quite interesting. I had some warning about what might happen because we discussed it during the risk assessment. A couple of journalists had been there before us—two Germans, a few Italians, and someone from the Washington Post—and the Russians had announced that they would ban those individuals from entering Russia.

While that wasn't my primary concern, I was surprised I hadn't been banned earlier, given that Russia had already banned certain journalists covering Ukraine, particularly defense correspondents based in places like London or New York.

After my trip, it became clear that the Russians didn't know who I was while I was there, but they certainly knew once we published the piece. A very bellicose statement was released from the Russian embassy in London, declaring that I was banned for life from Russia. I had already accepted that this was inevitable, and realistically, I couldn’t have gone to Russia anyway due to the situation with Evan; my company wouldn't allow it.

As much as I'd dreamed of taking the Trans-Siberian Railway to write about Russia and China's relationship, I had to let that go with the invasion of Ukraine. The statement from the embassy also hinted at potential criminal prosecution in absentia for journalists who had entered Russia illegally. While there weren't many details, I fully expect that process is underway, meaning I will be considered a convict in Russian eyes.

One of the legal experts we consulted indicated that Russia might seek an Interpol red notice against me. This is essentially an international arrest warrant, and Russia has a history of weaponizing these notices. An Interpol red notice serves as an alert for member countries to apprehend individuals on behalf of Russia. However, given the notoriety of this tactic, it's unclear whether European governments would act on such a notice.

This potential for an Interpol red notice has implications for my career, especially since I travel to countries that might be friendly to Russia. Some legal experts believe that Interpol would reject such a request, recognizing it as an obvious targeting of a journalist. Still, it leaves me with an uneasy feeling.

We’re keeping a close eye on the situation and may need to file a preemptive measure with Interpol to address any potential issues.

What a dramatic development this trip has been for your life—both personally and professionally. It has had a lot of ramifications.

I went in knowing the risks and considered them carefully. Interestingly, our legal director seemed more concerned about the possibility of being picked up by the Russians inside Kursk, which I didn’t find likely given the dynamics on the ground and the presence of Ukrainian forces. I was much more worried about potential legal repercussions after the trip that might impede my life and travel as a result of my visit.

One of the reasons I’m pursuing this project is that, despite all the advances in AI, there are still many ways people can access information without relying on human reporters. Thankfully, reporting isn’t one of them. I often tell people who claim that AI will replace journalists, 'No, it won’t.' AI can only generate content based on existing information. While it can utilize the insights we bring back from our reporting, AI itself cannot conduct reporting.

There you were behind enemy lines in Russia, not really knowing what you were going to find. And suddenly a Ukrainian soldier opens up a laptop. And a whole new world of understanding is revealed.

I did not know or predict that this would happen. I had no idea that this was part of their strategy to show Russian civilians what was really happening.

I want to do a quick lightning round. Your daily required reading list?

The New York Times, and obviously my own paper, The Times of London. I like to see how the New Yorker's homepage changes every day because they often flip something up that's pretty interesting.

I like to mix up the kind of running news. The stuff that's happening today with the longer reads. The Financial Times… my particular favorite is only once a week: “Lunch with the FT” and it's a fascinating way to get inside a personality, to sit down and break bread with them. I'm obviously an information junkie. I read a lot more than those, but those are the first hits of the day.

Your favorite opinion columnist?

Matthew Paris of the Times—he writes about politics and life, and his llamas. He has llamas. So you never quite know when you open a Matthew Parris column whether he's going to be writing about Israel, Gaza or mourning the latest llama to move on to llama heaven.

Your guilty media pleasure?

Oh God. Do I really have to admit this? I'm afraid it's the Daily Mail. I'm sorry.

Your favorite story by another reporter?

There was an absolutely extraordinary piece in The New Yorker by Rachel Aviv about Lucy Letby, the nurse who was convicted of killing babies under her care. I typically don’t follow crime stories that much, so this was the first I had heard of it. Like everyone else, I had taken her guilt for granted and viewed her as the face of evil. However, that story was mind-blowing because it introduced all the ways in which that conviction was unsafe. I would say it's the story that has changed my mind the most in a long time.

Your favorite country to report from?

I think probably Afghanistan, which is pretty impenetrable right now. I have been back once since the Taliban took over.

I just find it endlessly compelling and fascinating and you can still go to places in Afghanistan that feel like almost nothing's changed in about a thousand years and that's so extraordinary.

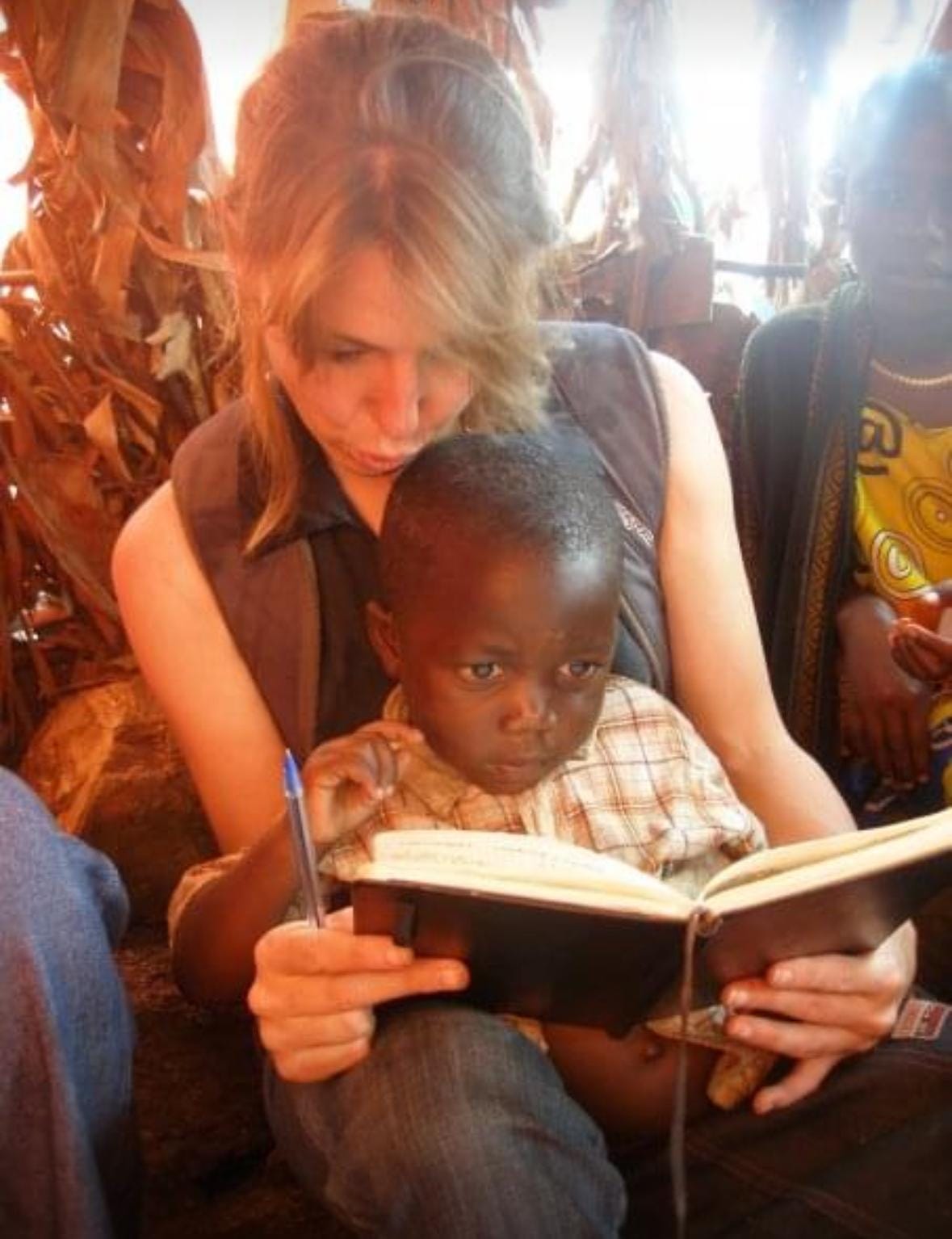

Southern Afghanistan, 2008.

There’s also the warmth of the people there that makes it such a beautiful place to be. I'm actually going back next month to the first place I ever reported from, which is Cambodia. So I'm pretty excited about that. There are places that hold that special place in your heart.

Helmand Province, Afghanistan, 2008.

You least favorite country to report from?

Oh, this is really difficult. God, I'm going to offend someone, aren't I? So I kind of loved reporting from America, but I also found it very frustrating, and again, this is about information spheres. I was based in Washington, D.C. from 2010 to 2013. And I found it really disappointing and difficult when you would go to places and be trying to report and people would just feed you lines that they got off Fox News.

This was the problem with information saturation. You weren't hearing what people actually really thought, you were hearing regurgitated lines. That's very difficult and disappointing as a reporter when you don't feel you're getting what someone actually thinks.

Words of wisdom for aspiring reporters out there?

Go out and speak to people. Don't let anyone tell you that AI will take your job away. Because as we discussed, we turf up information and reporting that is fresh and new and you can't do that any other way.

I'm a big fan of going out there and doing it myself. I still don't really feel that I've reported properly if I've only spoken to someone on the phone. And I think that probably comes from the fact I started in an era and in a country—Cambodia—and then not long after Afghanistan, places where you couldn't get someone on the phone, you had to show up at their house.

And I think that it does make a huge difference if you sit down and break bread, drink tea, look someone in the eye. I think you get a different level of reporting from that human contact. So just get out there and do it.

Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo, 2006.

What book are you reading right now?

I'm almost finished the last volume in a trilogy by Pat Barker, in which she is retelling the Trojan War stories from a female perspective.

So I'm now on “The Voyage Home,” which is at the end of the Siege of Troy and all of that. And there were two books, “The Silence of the Girls” and the “Women of Troy” were first, and this is the final one, and it's part of a fascinating development in literature, where women are taking stories that have only ever been known from a male perspective, and sort of re-energizing them through the silent female characters that we've never heard of.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Share this post