Last week, after a year of sustained fighting, Israel concluded a ceasefire with Hezbollah, marking an end to the worst period of violence between the two adversaries since the 2006 war. Whether the ceasefire will hold is an open question. Both sides have exchanged gunfire and mutual recriminations over the last several days, and despite the ceasefire, the Middle East remains a tinderbox. In Syria, rebels continue to advance against the forces of Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad, the Israeli Army continues to pound locations in Gaza, and Iran remains active across the region.

My guest today covered the Middle East nearly four decades ago. While in many ways the situation today is different, several of the main players are the same, and the situation across the region remains eerily, disturbingly unchanged.

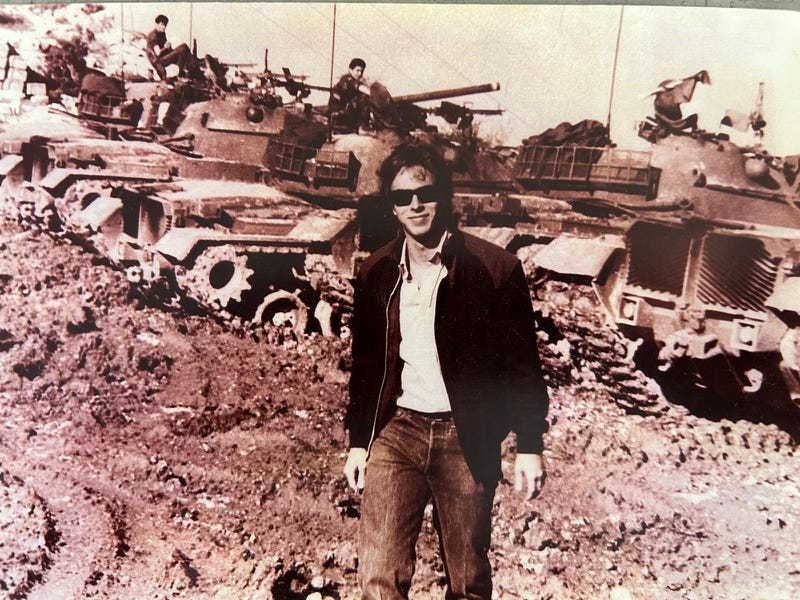

Michael A. Lerner worked for many years as a foreign correspondent for Newsweek and other publications, covering such conflicts in the 1980s as the war in Lebanon, the fall of Apartheid in South Africa and, in 2001, the war in Afghanistan. His film work includes the Brian Wilson biopic, Love & Mercy (screenplay), and the thriller, Deadlines (screenplay and co-directed).

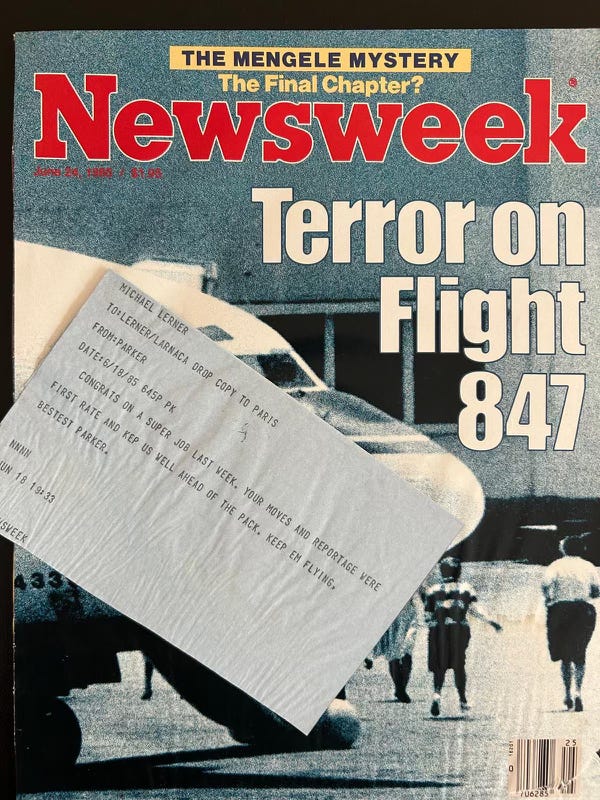

For this episode of The Reporters, Michael chose a story he wrote for The Daily Beast in 2020: “How Media-Hungry Terrorists Pulled Off the Wildest Hijacking of All Time.” Below are some highlights from our interview.

Michael Lerner, welcome to The Reporters.

Nice to be here, Scott. Bonjour.

Bonjour. Let's get into your fascinating piece, which appeared in The Daily Beast. You open with this amazing lede where you describe a series of terror-related events that occurred over the course of two weeks in June 1985. Take us back to those two weeks and that time 40 years ago. What was it like back then?

It was a different world. The Cold War was winding down and there was a vacuum. Suddenly you had this upswell of all these small groups that had grievances, that had irredentist claims on land and their way of expression was through terrorism.

So you had the Red Brigade in Germany. You had the neo-fascists in Italy. You had rebel groups in Nepal. An Air India 747 was shot out of the sky during these two weeks. There were bombings almost every day in different parts of the world. It was a very dangerous time. It was called the summer of terror in 1985. But in fact, it lasted for two years. It eventually quieted down, but it was quite a time to live.

It's extraordinary to think back to a world where terrorism was more multi-polar. There were many, many splinter groups across the Middle East and in Europe. They were very active in European capitals, Paris, Athens, Berlin. There were people like Carlos the Jackal…

Absolutely. You had the IRA…

As you point out in the story, there are a bunch of terror attacks that go off one after the other, each one more spectacular than the last. Up until September 11th, the Air India hijacking was the most deadly air attack in history — 329 people were killed. The airplane was blown out of the sky. All of these crazy things were happening and yet, as you say, Americans were pretty oblivious because something else was happening. Why? What happened?

We were wrapped up in our own hostage crisis. On June 14th, a Trans World Airlines (TWA) plane was hijacked from Athens airport. It was going to Rome and then scheduled to go to Los Angeles and San Diego. The plane was full of Americans.

It was hijacked by two Lebanese Shiites, Ali Hamadei and [an accomplice]. The plane took off, landed in Beirut, refueled, went to Algiers, went back to Beirut, went back to Algiers. It was basically a 17-day hostage crisis that gripped [America]. And what was so interesting about it was it really changed the media landscape.

"The vice president of TWA looked at me and said, 'How the f* do you know about that?' I remember my skin tingling. ‘Holy s***, there’s a bunch of Jewish passengers somewhere in Beirut, and no one knows it but me.’"

You had the advent of CNN. And for the first time, you had the capability of TV networks to broadcast live. CNN did — the other three networks weren't quite up to speed yet. The hostage crisis became this riveting phenomenon in America where 24 hours a day you were being broadcast what was happening on the ground.

That had a lot of implications. That's a lot of time to fill with content. This was a demarcation where news really became infotainment because of the necessity of filling this airspace. You had to fill it with anything that you could come up with. The Iran hostage crisis was of 1979 was sort of a precursor. This was the ugly stepchild.

We're going to take people through what you found. Before we do, it's worth noting that 40 years after the events that you described in the story, the world's gaze is focused on the exact same patch of land.

Israel invaded southern Lebanon. Bombs have been going off in Beirut, which is where this story takes place. Israel is going after Hezbollah, which is one of the terrorist organizations that you talk about. Talk a little bit about the historical echoes between then and now. [Israel and Hezbollah concluded a peace agreement since this interview took place.]

We are focused on the same patch of land with the same players, but things have changed.

Lebanon is basically divided into three main groups. You've got the Christians, the Sunnis and the Shias, each basically a third of the country. For a long time, the Shiites had been repressed and held back from power. That began to change in 1979 when Khomeini took over Iran. It gave birth to two groups. The first was Amal, a secular, Shiite movement headed by Nabih Berri, who plays into this story. It was founded by a cleric who disappeared in Libya a short time later and most likely was assassinated.

“A terrorist ran up the aisle with hand grenades. The pins had been pulled out. He was holding the hand grenades and the pins were in his teeth. It was a little detail that always stuck with me.”

Hezbollah's real beginning was after 1982 when the Israelis invaded Lebanon. That was the birth of Hezbollah, a religious movement. Hezbollah took its guidance from the Shiite revolution in Iran. At the time this story takes place, Amal and Hezbollah were building toward a war with each other.

Both at the time were funded by Iran. Today you have a situation where the players are much different. The camps have been solidified. You have Iran and its proxies. Hezbollah has become much more powerful than Amal. Hezbollah is a state within a state. If you look at the current situation, they have their own TV networks, they have their own healthcare, their own social services. They're not just a terrorist organization. They have greater military power than the Lebanese army.

The Shiites have gone from having no say at the table to dominating the Lebanese legislature through their military power, through assassinations, through exerting their military power. They are funded largely from Iran.

Israel played no uncertain role in Hezbollah's creation by virtue of occupying southern Lebanon for 18 years, which created tremendous resentment and led to so much of the antipathy that Hezbollah today feels toward Israel. So the players are the same. They have grown more powerful. There's also technology, as we've seen with Israel’s recent sabotaging Hezbollah's communications equipment. There used to be homemade rockets that they'd fire into Israel. Now they're ballistic missiles. So the stakes have gotten bigger, the death toll has gotten bigger, but the conflict remains the same.

And they've spent decades by now building a tunnel system that rivals, if not surpasses by several magnitudes of order, what Hamas has. That has added to the complexity of the situation because it's so densely populated. It's close quarters fighting there.

So, it's the summer of terror in 1985. Things are popping off all over the world. There's a hostage crisis in Beirut. There's a totally new media environment. Take us back to the beginning. What happened on that day in June?

So the plane is hijacked in Athens. It goes to Beirut. That's the first stop. We don't know anything about it. We just know a plane has been hijacked. I was a young reporter in Paris, working for Newsweek at a time when the written press actually counted for something, when magazines existed.

The good old days…

I was the second man in a three-man bureau, which is kind of inconceivable today. I was known as the fireman. When there'd be a problem somewhere, you would get flown in to help other reporters who were already on the ground. You were just sort of catapulted into a firefight. It was a great job when you were young.

[Early one morning], my phone rings. It's my Bureau Chief. There's been a hijacking. By the time I got to the airport in the morning, I met my photographer, Peter Turnley.

The technology of a reporter at the time was basically a notebook, a tape recorder and a shortwave radio. The BBC would tell you where the fighting was in Lebanon while you were in Lebanon. It would clue you into what was going on before the networks or any TV news found out. We're on our shortwave radio in the airport and we hear that the plane has just left Beirut.

“We didn’t have computers. We would file on a Telex machine the size of a desk with an AZERTY keyboard. It was survival — there’s no time for writer’s block in that situation.”

We don't know where it's going. We look at the flight board and there's a flight to Algiers. Turnley, who was more experienced than I was, thought, maybe it's going to go back to Algiers. And the reason was that Algiers had played a role in negotiating the release of the American hostages from Iran during the 1979 Iran hostage crisis. And they were trying to insert themselves in this story and present themselves on the world stage as the world's diplomat. That was in part to deflect from their own problems. We had about 20 minutes but the flight was full — except for one seat. There were two of us. I will forever be impressed by the wiles of an aggressive photographer.

He managed to convince the airline to give him the jumpseat, which was kind of amazing.

We fly into Algiers. We get there and there's no plane. We're like: “Okay, we're totally fucked.” And we're in trouble because we've spent all this money. About 10 or 20 minutes later, TWA flight 847 comes in for a landing. That was the flight. The airport is closed and we are the only two American journalists on the biggest story anywhere in sight. And we've got it all to ourselves. It was an amazing moment. It's obviously a horrifying story for the people on board, but there's an opportunistic element for journalists when they're presented with a scoop.

You and Peter commandeer an extra seat on the plane from Paris to Algiers, which by the way would never happen today. It's inconceivable. And I guess it was in part that lax security that made airlines such attractive targets for terrorists in the first place, right?

There were supposed to be three guys on the flight. They were Hezbollah. They exploited a loophole in Athens that allowed them to transfer directly onto the flight. They flew in from somewhere that had even more lax security. Athens was known to have fairly lax security. They had their guns on board, which is unbelievable.

Even in that era of lax security, it still boggles the mind that somebody could just walk on a plane with a gun.

And grenades!

So you're in Algiers. You’ve cracked the flight trajectory. You're the only journalists on the ground. What happens next?

We're in a hangar on the runway looking at the plane. I found out later through shortwave that before leaving Beirut, they had shot an American serviceman, Robert Stethem, who was 23 years old, who was a Navy diver.

About 17 hostages had been released in Beirut. That was the deal to refuel the plane. On board now was a really amazing purser named Uli Derrickson. She was an East-German refugee who would become American. She spoke German, and Ali Hamadei, who was one of the terrorists, also spoke German. And that's how they communicated to the pilot.

Uli Derrickson, the flight attendant, put 6,000 gallons of jet fuel on her credit card to satisfy the terrorists.

She really was heroic. She saved a bunch of the hostages lives by interjecting herself and preventing the terrorists from beating up people. I think they were really trying to get one of the other Navy divers killed. They wanted to kill one of the other Navy divers named Clint Suggs. She interjected herself between them.

It was a pretty brutal situation. At one point when the plane took off from Athens a terrorist ran up the aisle with hand grenades. The pins had been pulled out. He was holding the hand grenades and the pins were in his teeth. It was a little detail that always stuck with me.

I'm watching all this unfold and I see many of the hostages come off the plane.

You're at the airport. Are you able to move around? Are you on the tarmac?

I'm going back and forth. I'm with Turnley. We're listening to the shortwave radio. We're watching and we're waiting for whatever is going to unfold. Is it going to be resolved here? We didn't know. At one point, we saw the plane get refueled.

We later found out that the terrorists had demanded the fuel. The Algerians refused unless somebody paid for it. Uli Derrickson, this flight attendant, put 6,000 gallons of jet fuel on her credit card to satisfy the terrorists.

Did you have to do some finagling with the local officials to get access?

To the best of my recollection, I think the Algerians were overwhelmed. There were some local press that arrived. [Associated Press] arrived. Some wire service guys. Local stringers. I think they had other fish to fry. At one point they closed the airport. But we were already there. They didn't kick us out. We could move around relatively discreetly.

Besides Hezbollah, we now learn that there is another group of Shiite radicals who get brought into this saga. What happened?

The airport in Beirut was located in Amal territory. So you had Hezbollah, which was the religious Shiite, Iran-inspired organization. And you had Amal, which was the secular organization headed by a very charismatic guy named Nabih Berri. He was a lawyer who graduated from the Sorbonne, spoke fluent French, spoke English.

The situation on the plane was catastrophic. People were hungry, people were screaming. These two [Hezbollah] guys couldn't control what was going on. And they wanted to get Amal involved. They demanded that Nabih Berri come onboard and help out. He refused. He didn't want to get involved. At that point they opened the hatch and took Robert Stethem out and put a gun to his head and shot him and pushed him off the plane.

They said, “Unless Amal comes on the plane, we're going to start shooting hostages like we just did every 10 minutes.” That's why Amal ended up joining the hostages on the plane. They sent 10 fighters. They were very different from the Hezbollah guys. We used to call them “Gucci Gorillas” because they wore tight jeans and loafers and they were secular.

They were a lot easier to deal with than the Hezbollah guys who were much more serious and much more anti-Western.

What was Amal all about?

When Israel invaded Lebanon in 1982, as they were pulling back to the area of land they occupied in southern Lebanon, they took with them 766 prisoners, many of whom were just civilians and put them in Israeli jails. Hezbollah's demands to end the crisis was for Israel to release all of those prisoners, which Israel was not going to do. That's what they were asking for.

The difference was that Nabih Berri, the head of Amal, was a pretty sophisticated guy. He realizes that just holding the hostages isn't going to do it. He's going to enlist the greatest asset to resolving this crisis and getting what he wants — and that's the American media. He knew that if he played it properly and played it cleverly, the American media would do the work for him.

You and Peter Turnley are running around trying to get all the information you can with your shortwave radios. I want to stop there. Young journalists today, like all of us, have phones. The idea of traipsing around with a shortwave radio and getting tidbits of information from the BBC is just from another world. But I love it. And, and so one question, how did you file your dispatches?

We didn't have computers. We would file on something called a Telex machine, which was the size of a desk and had a keyboard on it. You would punch in your story, and often if you were in a place like Beirut, there'd be a line of journalists waiting for the Telex to file their stories. In the West, we're used to a keyboard that's a QWERTY keyboard. When you're in Europe, or parts of the Middle East, it's an AZERTI keyboard, which means the letters are completely different. So you can imagine, getting into the Telex, all set to type, and there's a bunch of guys who are not happy, waiting for you to finish, and you are hunting and pecking because you don't know where those letters are.

Would you write your draft of your story in your notebook before getting in line for the TELEX so that you would know exactly what your story was going to say?

If you had time. You'd basically write out a draft or write shorthand in your notebook and then sit down and barf it out on the Telex. Sometimes, you just didn't have time and you had to put it all together while you were in the Telex room.

Which again, is kind of extraordinary. It speaks to the importance of knowing how to write clearly and concisely, and how to quickly put your thoughts together. I would imagine that at the time that there was a real premium put on one's ability to not only think quickly when in a difficult situation, but to think quickly when you were tasked with passing on that information to your editors with 25 other journalists standing behind you.

If you didn't know how to do it fast you learn very quickly or you wouldn't last. It was survival. And a useful skill because there's no time for writer's block in that situation.

Eventually, as we learn in the story, some of the hostages get released. You figure out how to find them and interview them. How did you find them and what was it like interviewing them?

I'm watching the plane and at one point the rear hatch comes down with the ladder. I see these hostages start getting off the plane and getting onto a bus. Uli Derrickson, I found out shortly thereafter, had negotiated — in exchange for refueling the flight, and paying for the fuel herself — the release of another 53 hostages, women and children, old men. We're in day three now of the hostage crisis. They get on the bus. I ran out of the airport, got into a cab and said: follow that bus. We follow the bus. The bus pulls into a hotel. I waited in the cab and then went into the hotel and snuck onto their floor and started knocking on doors.

These people have been traumatized. It was not easy to get them to talk. But the funny thing is, sometimes people who you least expect to want to talk to you after having lived through a traumatic event, need to talk, for their own mental health.

They told me what had gone on, on the plane. It was very powerful for me. I had a lot of empathy for them.

They told me one story which stayed with me. At one point, the hostage takers had asked Uli Derrickson to collect all the passengers. Subsequent to that, a number of passengers with Jewish last names were called to the front of the plane.

When they originally hijacked the plane, they cleared out the first class and rearranged all the seats so that the men would be on the window and the women and children would be in the aisle. It made sense from their point of view. At one point, in Algiers, passengers with Jewish last names were called to the front of the plane.

I asked: “Did you see them again as you left?” None of the passengers had seen them. But the passengers had exited through the rear. I wasn't sure what was going on. After I did my interview, I went back to the airport. There was a TWA vice president who had flown in on a private plane to try to do something to help.

There was nothing he could do. And I got to know him a little bit. We were talking. He was very nice. And I said: “So what about the passengers with Jewish last names who got off the plane [in Beirut]? “

Now, I had no knowledge that this had happened. I was just bluffing. And he looked at me. He said, “How the fuck do you know about that? “

I remember my skin tingling, going, “Holy shit. There's a bunch of Jewish passengers somewhere in Beirut and no one knows it but me.” This was the biggest scoop in my very young career. I'd been to Beirut. I'd covered some stories, but I'd never been given a scoop where I was the only one who knew something that the world wanted to know.

“The situation on the plane was catastrophic. People were hungry, people were screaming. These two [Hezbollah] guys couldn't control what was going on.”

I left the airport. I commandeered a Telex and notified Newsweek that a bunch of passengers, possibly with Jewish last names, most likely were somewhere in the southern suburbs [of Beirut] at this moment, which was a big deal.

The plane subsequently took off. It went back to Beirut. I was left in Algiers. At this point, the rest of the world's press corps had flown in. Thomas Friedman, of the New York Times, who was based in Beirut at the time, a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner for his coverage in Israel, came up to me and asked me for a fill. (laughter)

I said: Sure, Tom, I'll help you out.

Explain to us — what is a fill?

A fill is when a journalist arrives late on a story and another journalist basically tells him what's going on and sometimes even shares a quote or two. I didn't share any quotes with Tom. Tom was capable to get his own quotes.

You talked a little bit earlier about deploying one of the tricks of the trade, I guess you could call it. In this case, it was a little bit of a sleight of hand, a bluff, and it worked because this vice president of TWA revealed something that maybe he shouldn't have, and it gave you a great lead to follow.

Later in the story, one of your colleagues pulls a fast one on you…

My direct competitor was Time Magazine. Time was late on the story, like everybody. The Time correspondent, Jim, had flown in. He was an old Africa hand, a lot older than me. There's a flight leaving Algiers to Paris that has a connection to Beirut. All the reporters had booked on that flight, including myself. There was some time to kill before the flight and Jim says to me: “Hey, I know this great little restaurant on the port where they serve lukewarm shrimp.”

We go down. We have lunch. It's great. It's delicious. We go back to the hotel. I feel this rumbling. Twenty minutes later, I'm exploding from every orifice. I'm in Jim's room. I was using his shower. He looks at me and he's like: “Oh, yeah, the shrimp. Well, I guess I'm not going to see you on the rest of this story. I'll call a doctor for you. But, take care.” He smiled and closed the door. True to his word, an hour later a doctor arrives and gives me these two mammoth shots in each buttock. Fifteen minutes later I'm up and able to walk without soiling myself.

“We are the only two American journalists on the biggest story anywhere in sight. And we've got it all to ourselves. It was an amazing moment.”

I missed the connection, but there was another flight to Charles de Gaulle, which is on the other side of Paris, without a connection to the Middle East. And this really tells you where the world was back then. The written press had money. Nobody had more money at the time than news magazines.

I arrived in Charles de Gaulle and I rented a helicopter to take me to Orly, and I made the connection to the Middle East. It was worth it just to see Jim's face when I walked down the aisle, still splattered in my same old clothes with little pieces of vomit everywhere and took a seat.

You mentioned the advent of nonstop cable TV news around that time. Today, not only do we have cable news, we have social media. Everyone has a phone. Everyone's a photographer. Information digestion has been amplified by several orders of magnitude. But what was that like going through that transition when print had ruled the day since the advent of journalism?

The Beirut hostage crisis was a demarcation point where the written press was basically cast aside. Nabih Berri was this very skillful guy who realized that images are much more important than the word. The written press was banished to the backlot. He knew how to exploit the media in a way that presaged what would become much more horrifyingly ISIS later on in terms of the power of image.

He sold himself to the American media as the negotiator, which was a little rich given the fact that it was his own fighters who were holding the hostages prisoner. The American media bought it because he spoke English.

So the plane landed in Beirut. The U. S. moved in an aircraft carrier, the Nimitz and another battleship off the coast of Lebanon. There was a rumor that Delta Force was going to stage a rescue. Under cover of night, Amal turned off the lights at the airport and all the hostages were taken off the plane and spread in different houses in the southern suburbs to preclude any kind of rescue.

“Sometimes people who you least expect to want to talk after a traumatic event need to talk for their own mental health.”

This is where the story got a little funky. You'd think that during a hostage crisis, with an aircraft carrier off the coast, the city would be locked down. CNN had moved in these two earth stations that allowed them to broadcast live. The three networks were struggling to compete and maintain their relevance. And the way they did that was outspending each other. CBS had two planes going back and forth from Cyprus to Beirut, to Paris, to London, to wherever they needed to get their tapes. They were all competing with each other.

There was a famous hotel called the Commodore. It was packed and booming. It was grotesque. ABC had parked itself at this luxury hotel on the coast called the Summer Land and they were they were well connected to Amal so they were getting a lot of scoops. Nabih Berri would trot out a bunch of hostages for interviews. He allowed ABC to have a fashionable lunch on the beach with a few of the hostages. Some of the hostages seemed to be getting into it as well. The hostages had nominated a spokesman named Alan Conwell, who was very erudite, he spoke a little Arabic, had lived in the Middle East for 10 years. He was in the oil business. He was very telegenic. He became known as the hostage who wouldn't clam up because he began to expound on all issues Middle Eastern.

As horrifying as this was for the hostages, it began to look ridiculous. The situation eventually resolved itself 17 days later. ABC and Amal threw a celebratory lunch for the released hostages at the Summerland Hotel, to which the hostages drove themselves in cars provided by Amal.

Do you think the black comedy element of it all played a role in somehow releasing the tension?

Yeah. There have been academic studies on this very subject, on this very case. It is not an unreasonable speculation to say that all the media attention prolonged the horror that these people were living through. Journalism is opportunistic. You see me gloating about my scoop. Imagine that from a network point of view. Their ratings are going through the roof. You have this crisis, you have American eyeballs watching this crisis, and their ratings are going up. Money is being made.

On the whole, when you put that event in the context of some of the more recent developments, let's say October 7th, it almost seems a little quaint — the idea of hostages eating lunch with their captors at a four-star hotel…

When I was covering Lebanon, yes, it was dangerous and yes, journalists died. But all of the different factions wanted publicity. Now the Middle East is a much more dangerous place.

As somebody who was in Lebanon and Israel 40 years ago watching this weirdly dark story that had comedic elements, how would you feel about going into southern Lebanon?

If I were a younger man, I would go, but I would be much more wary of the danger. Even by the end of my tours in the Middle East, kidnappings were rife of journalists. The world has changed. It's a much darker place now than it was.

Thank you for joining us. I think it's going to be a real treat for people to get the perspective of somebody who was there on the ground 40 years ago reporting on events that are still weirdly echoing in today's world in very different ways.

Technology has changed, journalism has changed. But there are still reporters out there doing the same thing, getting on planes, going to airports, trying to get the story, just the way that you did. I really appreciate your being here and your insights.

Thank you, Scott. It was a pleasure. It was fun.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and brevity.

Share this post