Deborah Bonello is an investigative journalist, writer and editor and has been based in Mexico City since 2007. She has reported extensively on organized crime, from criminal syndicates and markets, particularly drug trafficking, to violence and culture related to the criminal world. She was bureau chief of VICE News Latin America from 2019 to 2023, and over the last two decades has reported for the Los Angeles Times, the BBC, the Financial Times and the Telegraph, among others. She is currently a senior researcher and editor for the think tank InSight Crime, dedicated to the study of organized crime in the Americas. Deborah brings a rare gender perspective to coverage of organized crime. From the rise of the female protagonists she follows, to their experiences at the hands of the justice system, her work adds a new nuance to an industry whose history has been largely written by men. She is the author of Narcas: The Secret Rise of Women in Latin America’s Cartels.

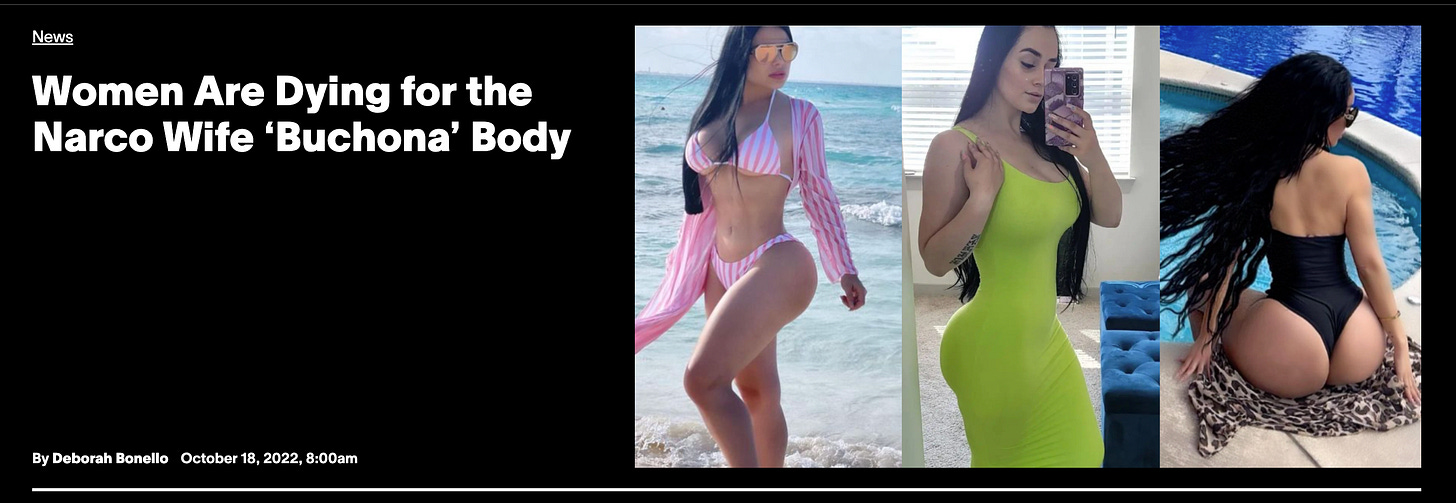

For this episode of The Reporters, Deborah chose a story she wrote for Vice in 2022: “Women are Dying for the Narco Wife ‘Buchona’ Body.” Below are some highlights from our interview.

Let’s get into it. You lead with a woman from Culiacán in your story. Can you set the scene and explain why that city is so central?

Culiacán is the capital of Sinaloa, and everyone’s heard of the Sinaloa Cartel. It’s where that cartel was founded and where it’s still based. Despite the arrest and extradition of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, the cartel remains powerful. It has fragmented into factions, one led by several of El Chapo’s sons. Since the so-called “drug war” began, extreme violence has ravaged Mexico, especially in areas like Sinaloa. Culiacán symbolizes how the drug trade has seeped into almost every corner of life. We've seen homicides go up and down over the last two decades, but since the drug war began, there’s been at an unjustifiable level. Some of that has to do with rivalry between different cartels, some with conflict between government forces and the cartels.

"The ‘buchona’ look is ultra-produced—exaggerated curves, lighter skin, and a certain type of nose. It’s a visual shorthand for wealth, status, and connection to the glamorous cartel lifestyle."

Also, social media in Latin America completely exploded. So you have this narrative around organized crime, a rags-to-riches narrative painting it as an aspirational lifestyle. A lot of people in the drug trade have become role models for young people around the region who exist in economies and societies where education levels are low, social mobility is hard, and class and social status are a huge barriers to advancement. People look for status and empowerment in all sorts of realms. And I think drug trade has kind of provided that.

You lead with this woman, Paulina Garcia. Tell us about her. What does she want?

She was this working-class girl who wanted what they call a “mini lipo,” where fat from your tummy is moved to your butt and breasts for the extreme hourglass figure. Locally, it’s part of the “buchona” or “narco wife” look, which is basically very accentuated curves. It’s also a way to show off that you can afford plastic surgery. She went to a dermatologist who was presenting herself as a plastic surgeon and offering cheaper prices. Unfortunately, she went to someone with questionable qualifications, got septicemia, and died.

What exactly is the “buchona” aesthetic?

It’s an ultra-produced look associated with the narco world: exaggerated breasts, a tiny waist, a big butt, often lighter skin, a certain type of nose. You see it on social media, promoted as aspirational — if you look that way, you appear to be part of this glamorous cartel lifestyle. It’s popular in Colombia, Venezuela, the U.S., and has roots in beauty-queen culture in places like Sinaloa. The narco wife look has proliferated across the internet. It's mainly propagated by Emma Coronel, who is the very young wife of Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, one of the founders of the Sinaloa Cartel. It's kind of Kim Kardashian on steroids, before Kim Kardashian took out her implants. Because of the opacity of Mexico's system and the way that deaths are registered, it's hard to quantify how many women are dying from botched surgery in Mexico. But it's certainly a thing. Plastic surgery is very, very prevalent in Latin America and has become very acceptable and commonplace for women.

Why would these women go so far for this “narco wife” appearance?

It’s about status and empowerment in that local ecosystem. If you look like that, people assume you’re connected to someone with money, possibly a trafficker, possibly not — but you look the part. It can elevate you socially and financially in a place where climbing out of poverty is otherwise really hard. A lot of women get surgery funded by husbands or boyfriends. Some even receive it as a gift. It’s common enough that entire payment plans or group savings schemes are built around it.

Can you talk about social media’s role in spreading this?

Social media amplifies it. There are endless Instagram accounts promoting the “buchona” image — photos of women posing in luxury settings, showing off surgically altered curves. It suggests you can transform yourself into someone important. Meanwhile, cartel-linked accounts flaunt weapons, cars, and the narco lifestyle. It sends a message to young men and women that they could achieve wealth and power in a society where legitimate opportunities might be scarce. In the U.S., a lot of artists are pushing and using that look, which is super, super produced. When I was researching Paulina's story in Culiacan, I spoke to a few women who had had surgery and they said that a lot of women come from the States to have surgery in Culiacan because doctors will go a little bit further.

They talked about the process of taking out the lower rib in each rib cage so that the waist can be pulled in smaller. A doctor in Culiacan told me, “There's no scientific proof that that does anyone any harm.” My reaction to which was like, well, we have those ribs for a reason, right? But okay. Mexico is a more informal culture where the rule of law is weak compared to somewhere like the U.S. Women who have the will to take things that step further might come to Mexico because it might be easier here.

Let's say Polina hadn't died and she'd gotten the surgery, what would have been the natural next ambition for her? Was getting the surgery a step towards some greater aim or was it simply to be part of a social class that she didn't have access to? Would it allow her to get a husband or something like that? What was the end goal?

It's all of those things. On one level, she's living in an ecosystem where drug trafficking has become a way of life for many people. And so if she looks like that in that ecosystem, her chances of attracting a man with money are higher, whether he is himself in the drug trafficking business or not is kind of beside the point. And I should emphasize, there are a lot of people who look like traffickers in Culiacan who aren't. It's really kind of like the rap movement in the U.S. with the drop-waisted jeans and the hairstyles and everything. A lot of people adopted that look when they weren't rappers. It's also the same reason that women have surgery.

"It’s not about being a narco wife — it’s about looking like one. The aesthetic projects wealth, power, and connections, even if they’re not real."

Men also do this in Culiacan to a certain extent. It's looking the part and wanting to kind of feed into an aesthetic that is seen as hip, empowered, wealthy. An academic told me, “It's not about being a narco wife, but it's about looking like a narco wife because people think you're cool, they think you're connected, they respect you more.” I think those were probably her motivations. It was probably quite subconscious. If you've grown up in the state of Sinaloa, in the city of Culiacan, from the moment you are out of the womb, you're being embedded in that culture. The attorney general once told me that she was in a salon once in Culiacan and a woman walked in and said, “Make me look like Emma.” And she was talking about Emma Coronel.

So who is Emma Coronel. She's the figure that looms not only over this story, but over this whole world.

Emma is a young Mexican-American. She's dual nationality. She was born in the United States and then raised in part in Mexico. She met El Chapo when she was just 17 or 18, when he was already on the lam. Whether they fell in love or not is anyone's guess, but she became his very young wife and presumably they had a very unconventional marriage because he was already a fugitive so how much they got to cement their nuptials, I don't know. Emma was also the daughter of a prominent Sinaloan trafficker. Marrying El Chapo was rather like marrying a major CEO if you're born into the business world. She's very much capitalized on that on social media and built herself up to be the sort of archetypical narco wife.

She has all those physical assets that I was talking about before. After her husband was extradited and convicted, she herself was taken into custody. She was sentenced to three years for her role in Chapo’s criminal enterprise. Before she was put in prison, she was on the Cartel Crew series on VH1, sipping champagne on the decks of glamorous yachts in the U.S., telling her experience of being part of that world. People are fascinated by it because it's so opaque. What we understand about organized crime is largely fed to us by journalism and Netflix and fiction to a certain extent. Some of it is just very fantastical, but people can't sort of get enough of it and get enough of her and her stories. So she's very much sort of seen as the female face of the Sinaloa Cartel, but she was not terribly powerful in terms of the decision-making process.

How did you get into this world?

I tracked down Paulina's family through a local journalist who worked with me on that story. And Culiacan has a very big beauty queen culture too. There are a lot of plastic surgeons. I had a really good contact there with a woman who's done a lot of plastic surgery. She spoke to me extensively about the kind of work that she had done. Through her, I managed to kind of get a lot of kind of insight into the way that people think about plastic surgery and the drug trafficking world and the connection between the two. People think of the narco world as being this very bling lifestyle, but the people who aspire to it or the people who are influenced by it come from very precarious financial and educational situations. I was very struck by those extremes.

You talked about how it's exploded on social media. I would imagine that especially for that demographic, that's a very potent collision.

If you go to Instagram and type in “buchona,” you will see hundreds of accounts of beautiful photos of women who've had work done. It’s deeply filtered and edited. All of those women are in swimming pools and beautiful hotels and places that suggest that if you look like that, then those places will become your environment. There are also lots of Instagram accounts that talk about pre-surgery and post-surgery care, and they're very much pushing this trend and educating women about the process of having plastic surgery and how to recover from it. There are lots of horror stories too.

"In an ecosystem where social mobility is hard and class barriers are rigid, looking like a narco wife can elevate you socially and financially. It’s about survival and empowerment within that system."

On a broader scale, the cartels have seized upon TikTok and Instagram to show off their weaponry and broadcast the riches that drug trafficking can afford. Those things are interconnected because the women who are having surgery then appear in the music videos and they appear on the arms of these men. Remember that Sinaloa is a very traditional agricultural state. Women are as powerful as the men that they're attached to. So the importance and power of their men is intricately connected with their importance and power. It's hard to overstate quite how powerful social media has been in that.

A few years ago, the New Generation Jalisco Cartel, which is probably the biggest rival and one of the strongest cartels in Mexico after the Sinaloa Cartel, were showing tanks and barrels and weaponry in a line up. The camera was going down a line of tanks with masked men, heavily armed, weaponry that rivals Mexico's military as a show of strength. That fuels recruitment. Young men and women see that and they want some of that. Even though they understand that the lifespan for those cartel henchmen is hard and short.

Your deeper reporting goes beyond the “buchona” look. You’ve written about women in the cartels who actually run things. How did that begin?

I’d been covering organized crime for years, and the usual narrative focused on strong male figures like El Chapo, with maybe a pretty wife in the background. But I suspected there were women who weren’t just accessories — women with serious operational roles. When I started looking, I found many who’d been key to smuggling routes, money laundering, even delegating violence. They just kept lower profiles and didn’t get media attention.

As a journalist, what is it like to report on this stuff? Mexican journalists who come near this are really in grave danger and there've been a number of murders and assassinations.

I think as foreigners we are in a different category. We're far less vulnerable than Mexican journalists are. I also think the people who read and consume my work are sort of voyeurs, policy wonks, but they're not the people who I'm actually writing about. If you're a local journalist writing about local corrupt judges or policemen or how the cartel is controlling the lime industry, you're much more vulnerable to retribution than someone like me whose work is being read by people in the U.S. and Europe. And that spares me to a certain extent.

Having said that, the women in my book didn't love the book, which feels uncomfortable, especially when you know that at some point in their lives, those women have been empowered to send out contract killings and they have been delegating violence to other people.

"Plastic surgery is very, very prevalent in Latin America and has become a marker of social status. It’s common enough that entire payment plans or group savings schemes are built around it.”

I wouldn't write a book like this again, to be honest. I've been in Mexico for 20 years now. Your enthusiasm and appetite for risk shrinks, or at least that's been the case for me. I'm not sure it really achieves anything anyway. I do see impact from our work, but there's so much more content and so much more reporting on these things that it's way easier for things to get lost, which to me is like even less reason for me to take any kind of mortal risks.

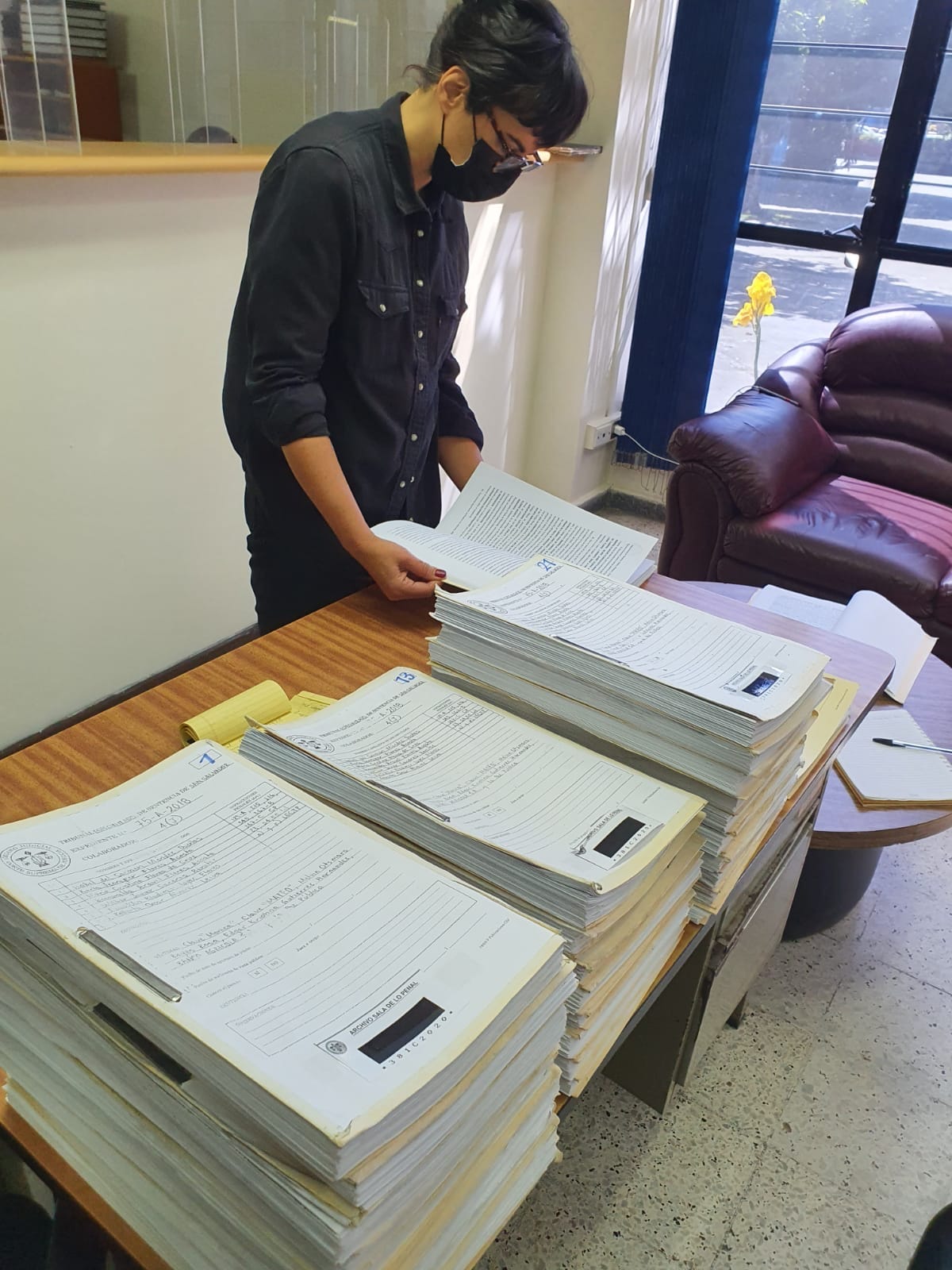

And I think the perception of investigative reporting on the cartels is also a little different to the reality. I spend hours, weeks at my desk going through legal documents, talking on the phone, interviewing lawyers and experts. Yes, there was field work, but the field work is always very well researched. There was some magic in the field on the reporting, but as a reporter, you never go into situations that you don't think you have a chance of coming home from it. And I think people have that idea. It's very different going to report from the frontline in Iraq or Syria. Of course there's some unpredictability, but it's different. I think with preparation, you can really reduce risk significantly. The challenge for me was not having really anticipated what the impact of the book would be once it was out.

Deborah reporting outside of a prison in Guatemala

How did you track down these stories without putting yourself in danger?

I rely on court documents, lawyers, people in the legal system, and carefully planned field reporting. Local journalists face huge risks, especially if they cover specific local corruption or name certain officials. As a foreign reporter, my risk is different, but it’s still difficult. People are wary about talking, so I often have to piece together what happened from multiple sources and records.

Let's talk about your book. How did you stumble into the idea of doing a project on Narcas, the women in the leadership positions or in the top positions in the drug trade?

It came from being an unconventional girl and growing up around the tropes of what we should do as opposed to what I wanted to do. I've always shrunken away from gender tropes. When I arrived in Latin America 20 years ago, the violence around the drug trade was always part of general news coverage. The longer I was here, the more I focused on that. It was very apparent to me early on how the women we were seeing were women like Emma Coronel. But I felt like it just cannot be possible that we're seeing women rise up in football and tech and finance and that there aren't more women involved in the business and the logistical side of the drug trade. In Mexico, women are increasingly moving into the workforce in the licit realm. So it was my guess that it had to be taking place in the illegal world too. The more I looked, the more women I found. That's what got me going.

“As a foreign reporter, my risk is different, but it’s still difficult.”

Very few of the women responded to my requests for interviews. I had very limited access. So a lot of what I constructed in the book was from people who knew them, like criminal lawyers who work in that field and all the legal documents around their cases. And from that I was able to piece together enough to write Narcas. A lot of those women just don't want to be in the public eye. They don't want to talk about it. A lot of them have done their time and now they're trying to get special visas so they can stay in the U.S. and not come back home to hostile criminal organizations that have seen them talk to U.S. prosecutors for the last decade. It's really hard to get into their minds.

Why is it so hard to find information on women in cartels?

They’re not the stereotypical big bosses we see in the headlines, so people don’t think to look for them. They might be older, look like ordinary mothers or grandmothers, and they deliberately avoid the spotlight. Even so, I found cases of women who had college degrees, business or law backgrounds, and used those skills in drug trafficking organizations. They’re not all coerced or victimized; some are very much in charge.

What was the most surprising thing that you discovered about these women?

There is this very kind of bad guy narrative about the drug trade, how the people who get into it are these sicko psychopaths determined to destroy the lives of young Americans. And you're like, no, man. These people lived on a border in a very poor town. They used to smuggle cattle and tobacco across the border. When cocaine started flowing from Colombia, north into the United States, opportunity really came knocking. It created these industries and these opportunities to make money. Prohibition helped them because it made that product much more valuable than cows and illegal booze. For a lot of people, it was just the flow of life and how things come to them.

"Social media amplifies the ‘buchona’ aesthetic. It suggests that if you transform yourself to look this way, you can be someone important, someone respected in a world where opportunities are scarce."

One of the women was the eldest of 13 siblings and her entire family were involved in the drug trade. Then she brought her kids into it and her neighbors and her village. Her family were huge patrons of that community and they set up businesses and bought a lot of real estate. They provided jobs to people who are living in grinding poverty and whose options were either to migrate to the U.S. or earn a pittance in the agricultural trade. When you see Griselda, for example, the Netflix series, you see very little of their origin story and I think that's fascinating because it really messes with this idea that people are born bad and they just want to be rich at any cost. It’s so much more complicated than that.

Quite a few of the women in the book were educated women. They could have done something else. One of them was a lawyer. Another was a businesswoman with a college degree. For whatever reason they chose to swerve into the illegal trade. And someone said to me that Marjorie Chacon, who at one point the Treasury Department says was Latin America's most prolific trafficker, if she had been in the licit world, she'd be like one of the top COOs or CFOs. It just so happened that she chose to apply those skills to the illegal business.

Were the women that you tried to speak to for the book surprised that you were interested in them?

Yes, they were. Most of them have kept a really low profile. One of them was the right-hand woman of one of Chapo’s sons in the Sinaloa Cartel. She was first covered by the Chicago Tribune when she pleaded guilty in Chicago. And then she just disappeared. All the stories were about her arrest and her plea and that was it. I went to Pacer [a database for federal cases] and her entire criminal history was there. No one had really looked into it. She'd been working with Alfredo, one of El Chapo's sons on every link of the chain from corrupting government officials to moving product into the U.S. to laundering money in the U.S. to moving value back to Mexico. She was absolutely vital for the daily running of the organization.

I'm kind of struck by the sense that maybe in reporting this story, I wonder if it gave you an added understanding about journalism itself?

I'm Maltese, brought up in the UK, a kid of immigrant children, one of four siblings. When we go and cover something, we think we're like a blank slate. But I think we're kidding ourselves if we think that that's what's happening. I was married to a Mexican for 10 years. I was very immersed in Mexican culture and the Spanish-speaking world. And I think if we're English speakers coming to countries where we barely speak the language and yet we're writing these stories about cultural issues or crime, we're kidding ourselves if we think that there's only one version of that.

It's naive to think that how we present things is the only way that they are. It is kind of mind-blowing to understand just how much of our perception of the world is determined by where we're coming from and where we're standing and what our editor in New York wants and what he or she thinks is going to get clicks online and everything that feeds into the way that the media presents and covers the world. That has kind of been a big eye-opener for me as I get older. Our expectations do sort of determine the way that we perceive things and how we interact with them. And if we just loosen up a little bit, there's so much else that we can see and understand.

Deborah doing research about the “Black Widow” for her book about the rise of women in Latin America’s cartels

The older I get, the less inclined I am to judge people's opinions, even if I don't share them.

I'm very aware of the gender disparities in the legal system and of women's access to justice compared to men's. I'm acutely aware of all of that stuff. But this idea that poor people are always good, rich people are always bad, women are always victims and incapable of malice, this is just fantasy.

I feel like we should be saying more, oh, well, that's interesting. That's not where I've come to, but I'm interested to know how you've come to that belief and why. And a lot of the time when you ask people, it might fall apart, but a lot of the time they have good reasons for it.

I couldn't agree more. I think that's an important lesson just to be a human being, but an especially important lesson for anybody aspiring to be a journalist.

People are very willing to be offended very quickly. If we can be a little less concerned about being right all the time and just be a little bit more curious., I think we'd have a very different political climate and media climate. Life is very rarely simple.

Thanks so much for coming on the show.

Thanks Scott, I really appreciate it.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Share this post