My guest today is Kathy Gannon, who reported for the Associated Press for 35 years, covering Afghanistan and Pakistan as chief correspondent and later news director. Gannon was the only Western journalist allowed in Kabul before the 2001 U.S.-British offensive. She also covered the Iraq War, the 2006 Lebanon War, and the Central Asian States.

In 2014, Gannon was critically injured while covering Afghan election preparations when an Afghan police officer opened fire on her car.

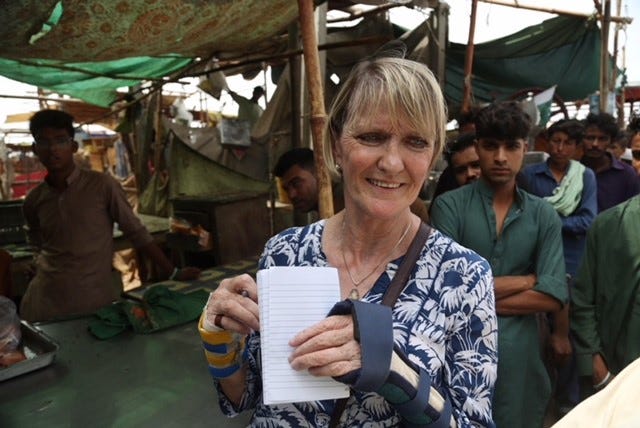

A Canadian native, Gannon has received numerous honors, including the 2022 Columbia Journalism School Lifetime Achievement Award and the IWMF Courage in Journalism Award. Since 2022, she has been looking at how we do our journalism and the compromises to our independence.

In 2025, Gannon will be teaching at the University of Western Ontario, London, Canada.

For this episode of The Reporters, Gannon chose a story she wrote for the AP in 2017: “Islamic Schools in Pakistan Plagued by Sex Abuse of Children” Below are some highlights from our interview.

Kathy Gannon, welcome to The Reporters. It's great to have you here.

It's great to be here. Thank you for having me.

You picked a story for us that you wrote in 2017 about sexual abuse in Islamic schools in Pakistan (called madrassas). You start the story with a woman recalling something that had happened. Tell us what she said and what that interview was like.

I had actually traveled down to the south of Pakistan, the Punjab. She was the mother of a young lad who had been raped. He had blood on his shalwar, which is the baggy pants that they wear. It took a while to get him to talk. It’s what is so heartbreaking in these stories. It's very similar to the sexual abuse in the Catholic Church. That's a lot of what got me thinking about this. It's a very difficult story, just as it was very difficult for victims to come forward from the Catholic Church.

There's a real fear. And also children are so afraid to speak up because they're made to feel ashamed. In every society, religious people are held in such high esteem. And even though people have heard of it and understand that it happens, they really don't ever think it happens to them.

"Once they rally around each other, they seek to discredit the child, discredit the family, discredit you."

I think this is why it got so hard to tell these stories — not just to find the victims, but they'd follow it through. And this was really important to me — to follow through on these cases and to go to see the Mufti that was accused and who ended up being charged. And who ended up going to court. And like in the scandal with the Catholic Church, all the other clerics rallied around this cleric. And so that also became very much a part of the story and became very difficult one to tell. Once they rally around each other, they seek to discredit the child, discredit the family, discredit you. Your neighbors are talking. Your neighbors are hearing about it.

Reporting from a village in southern Sindh, Pakistasn, where victims of a suicide bombing lived

It must have taken a huge amount of work. How did you get access to those victims who would have been reluctant to talk?

It took me a long time. I kept going back again and again. There was an organization, Sahil, which looks at statistics of abuses and does a remarkable job of calculating the numbers of abuses through stories in the local newspapers and then follow it up with police reports. I had a number of police reports that I was following through on and double checking. I found that there were certain areas with more cases. There is a lot of initial work done in terms of locating documentation, locating information, locating figures.

“It's very similar to the sexual abuse in the Catholic Church.”

There isn't any more acceptance of this happening here than there is of it happening anywhere in the world, and among any religious group. The police aren't as helpful as they can be. The families also are reluctant to talk. The children are reluctant to talk. You have to keep going back to build that trust. You keep coming back. You get a little bit of the story, but you don't get it all the first time. You just get hints. Anyway, I located the particular religious cleric and gradually was able to put it together. And the more you could put together, then you go to the family. And then I talked to other children around there who had heard the stories or had seen him crying. Then it comes together as a story like in any way you try to put a story together. There's so many layers to it. You have to be really accurate because you can't be making these accusations.

And then going to the court and the court was in itself a little...unnerving because the cleric was surrounded by other clerics who were protecting him, and from some organizations who have a reputation of violence. So you're aware of that as you're doing this. I felt it was such an important story because of the coverage of the abuse in the Catholic Church. And I think that very idea of clerics and the trust that children put into clerics, regardless of the religion, and how that is then abused. To AP's credit, they were really supportive because it was a lot of trips and a lot of going back and a lot of research that didn't really result in a story for a while. And they were very supportive of me.

Kandahar, Afghanistan

People who are tasked with investigating these crimes are sometimes targeted for retribution from the madrassas and clerics, which creates a climate of fear and tension. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Some of them belong to groups that have a reputation for violence and there is a reluctance among the police to file the cases, partially because of the fear of retribution and threats but also the reluctance to want to tarnish the image of the clerics. They’re torn. You don't want to protect them, but at the same time, you don't want to tarnish who they are because you too grew up in that environment and you too grew up with that respect and that trust.

But because there are religious organizations that do have a reputation for violence, they can be very intimidating for people, and particularly for law enforcement and for anyone who would choose to confront those who are accused of this.

Documentation is difficult to come by. So you also have to be specific. What if people aren't going to charge? Then how can you say this really happened? You can't be sloppy. You can't be any sloppier in your work here than you are in America or anywhere else. You have to be strong in your documentation, your assurance that this is accurate, that this is double checked. That's part of why it takes so long, but it's also part of why it's very difficult to get the story and why I don't know that very many people have done this story. I think we might be one of the few that have done it.

This is obviously a huge problem not just in Pakistan, but I would imagine across the Muslim world.

You're absolutely right, Scott. Catholicism has a central [authority] and everything was fed back to them and they quashed investigations. That’s very difficult in the Muslim world or Jewish world because it's much more decentralized.

In Pakistan there's a bill being debated right now that would weaken government oversight of these schools. In the years after you wrote the story, some regulation was imposed. What happened?

There have been different attempts by different governments to regulate the madrasas and the curriculum so that students receive proper education from grade one through grade twelve. So they read, they get their sciences, their maths, their history, their geography. Then their religious training can be separate. But clerics in Pakistan are very strong. There are many different ones representing different schools of thought in Islam. There's the Sunnis and the Shias, but also within that there are different sub-sects.

There are five sort of basic schools of thought. Each one says, “Well, we can teach what we want.” The effort was to try to regulate them so that it would increase the education level. In some of the madrasas, sectarianism has developed. The government has been concerned. It's a real problem because Pakistan has been sort of the seat of a proxy war between Iran and Saudi Arabia. The Saudis have helped finance the Sunni extremists. The Iranians have helped finance the Shia extremists. Pakistan has been caught in the middle.

"You're putting all these young men out on the street with no skills other than religious teachings and nowhere to use that training."

This latest bill would further weaken what is already not a particularly strong bill, to reduce even the limited amount of control that the government has over them.

Pakistan doesn't elect religious clerics to govern. Yet people are very religious. There's no question. But they don't want them in politics as such. But these clerics have a great deal of influence. They can bring people out onto the street.

There have been different real bouts of sectarian violence. The effort has always been to try to limit these religious schools' ability to foster that sectarianism. The clerics are fighting that.

Kathy interviewing former President Hamid Karzai, Kabul, Afghanistan

The Pakistani military's media wing did a study recently and found that more than half of the country's religious madrasas were unregistered. The details of their financing remained unknown.

There were areas of Pakistan where you didn't have a lot of religious schools and then, suddenly, they were just really proliferating. It was sort of known within the local communities where the [funds] were coming from. In Afghanistan, during the Taliban's first rule between 1996 and 2001, I remember them saying, you know, we don't need these Saudis to tell us how to be good Muslims. There has been a lot of Saudi finance, official or unofficial.

Is there an obvious agenda to use the schools as indoctrination tools without the prying eyes of government oversight? Or what is going on?

No, I'm not sure that there is some secret agenda to have an army of young kids who are ready to take up arms to fight. I think that stereotype has been overplayed. But I think the lack of regulation does allow for sectarianism to grow.

Instead of fostering a tolerance, it's fostering an intolerance. They don't want anyone overseeing what they're teaching. It's not that they're gonna graduate this army of others, but they're gonna graduate this army of young people who have no skills to get a good job. They've been in school for 12 or 13 years and they've only had religious teachings. There's not enough mosques for them to then become Muftis. You have this legion of young people out looking for work that they're not qualified for.

You're putting all these young men out on the street with no skills other than religious teaching and no place for them to be able to use that religious training. So what do all these young people do? And young people who maybe are less tolerant to the other. Well then they become easy prey. The idea is to regulate these schools so that they do teach the students skills that they can use.

At the time of publication, there had not been any arrests. Earlier, you alluded to the fact that actually there have been some arrests. Can you talk a little bit about how that landscape has evolved?

There are some arrests but it's very limited. When they do arrest them, they often have this support group. These groups do carry a lot of weight at the village level. They can cause a lot of violence and very threatening behavior, not just to the police. They can bring out thousands of young people in the name of religion. Then that takes on a life of its own. It makes it very difficult when the police want to prosecute these clerics.

“Our job is not to cheerlead for the West, for democracy…our job is to try to understand."

They rarely stay in jail for any length of time. It's very difficult for judges and police because they threaten the judges. And then the judge is afraid to give a guilty verdict because they’ve been threatened, their family's been threatened. They weaponize religion. It’s easy to incite people in the name of any religion.

It's complicated by something else that you discussed in the piece, which is that the assailants, the clerics, the mullahs in these schools can be forgiven by the families with a bribe — blood money?

There has been some legislation to try to counter that. Say you kill me, but then my brother forgives you. You don't go to jail, but you pay blood money. There is a provision in the law. The charges drop.

This was a real big issue in the case of honor killings where a father or brother would kill their daughter or sister. And then they would be free because the brother who killed his sister would be forgiven by the father because they didn't want their brother to go to jail or suffer.

“An Afghan doctor saved my hand because he used duct tape and wood.”

The government just a few years back put in legislation that says even if the person is forgiven, the government can file the charge. The only thing that can be forgiven is that the death penalty would be taken off the table, but you would still spend life in jail.

In your experience, is that a system that leads to real healing or justice? Is it effective in other words?

I don't know. I think for me to make a judgment would be unfair. Perhaps some people in fact do find some healing. I don't believe in the death penalty. So do you want to ask me now, what do I say about the person who shot us? Does that lead to healing?

Reporting on COVID-19 victims, Kabul, Afghanistan

You've been reporting from the region for 40 years now, if I'm not mistaken. You've reported from Afghanistan, before the Taliban, during the Taliban, after the Taliban, Taliban 2.0. In that time, you've had your share of run-ins as a reporter. Can you tell us a little bit about the perils of working in that part of the world and maybe talk a little bit about what happened to you in 2014?

There are perils, obviously, working in conflict areas. I was in Iraq and in South Lebanon in 2006 for the war. You certainly have the dangers, but it's also the dangers that the people who are living there are going through all the time. Having covered Afghanistan for maybe 38 years, I've had so much that has happened. People say that this is horrible. I say Afghans have suffered horribly.

But what happened… Anja Niedringhaus and I were covering the elections in 2014 in Eastern Afghanistan. Anya was a really good friend of mine. We wanted to go someplace where you could really capture the determination and resilience of people and their determination to vote, even though the corruption was enormous. She hadn't been to Khost before. We arranged to go there. We were very careful about the security. We had checked the road. The UN had been through there. We were in a police compound in a place called Tanai, a 30-minute drive from Khost, which is a stronghold of the Haqqani Network.

“We in the West tend to define ourselves by the best of ourselves. And yet we seem to define everyone else by the worst of them.”

We had driven in a convoy. We made sure we were in the middle. There was police, there was army. We had done a story about these Afghan police. We had interviewed them. Anja had taken her pictures. One of the last pictures she took was a first aid kit they had. It had nothing. There was some gauze and a few bandages. I remember saying to Anja: “These poor things, what if something happens? They have nothing.”

It started to rain. We got into our car. Anja and I sat in the backseat. I was on the right, she was on the left, but she was sitting right next to me because she had put her cameras beside her. Anja and I were just sitting and talking. Anja had lit up a cigarette.

Our driver heard a policeman cock a Kalashnikov. Then he just emptied his AK-47 into Anja and I. I was hit with seven bullets. Anja died immediately, which I didn't realize at the time.

First I thought a bomb had gone off under our car. There was a lot of blood and stuff. I could smell the sulfur. I didn't know Anja was just leaning against me and we were just sort of leaning against each other, but neither one of us had fallen over. When they heard the fire, everybody ran away thinking maybe there was a suicide bomber. [The shooter] just put his Kalashnikov down and then they attacked them and arrested them.

We had never met him. We hadn't talked to him in the compound. The Taliban at the time said, “Listen, we had nothing to do with it.” There was some talk later that he had a connection with Gulbuddin Hekmatyar’s group.

He was sentenced to death. Anja's family doesn't believe in the death penalty and I don't believe in the death penalty. We both said the death penalty was off because a victim’s family can decide that — as long as he spends the rest of his life in jail.

Unfortunately, he was let out.

We in the West tend to define ourselves by the best of ourselves. And yet we seem to define everyone else by the worst of them. The worst of one nation is no worse than that of what happens in our own countries, I think.

Kathy and Anja in the mountains that border Afghanistan. They are the only journalists to have embedded with the Pakistan Army.

I'm so glad that you're okay. Did you ever find out any more about the assailant?

Initially, he said it was because there had been a bombing in his village and people were killed. They investigated and there had been no bombing. He was really kind of a belligerent sort. I didn't find out Anja had passed away until I had been medevaced to Kabul. They were helicoptering us from the forward operating base, Camp Chapman, where those CIA people had been killed in a suicide bombing a few years before.

An Afghan doctor saved my hand because he used duct tape and wood. I remember him saying to me: “I just want you to know that your life is as important to me as it is to you.”

I'm very sorry about Anja, your friend.

Thank you so much.

When you were reporting on the madrasas, you ran into some intelligence people at one point who asked some questions. Can you talk a bit about that?

Everybody is focused on Pakistani intelligence because they believe they're somehow more rogue than anyone else. I was told I had to leave a particular town. I was escorted out of the town. Then they stayed overnight and made sure that I left in the morning. And then they've come to my house, they've asked what am I doing?

I have a residency card that allows me to stay for five years at a time. There was a lot of problems with that at one point and I think it had to do with these stories that I was doing specifically on the religious schools.

Are you up for a quick lightning round?

Okay.

Your daily required reading list?

First I go through the newspapers online, always. I'm also right now reading Ann Cooper, Larry Heinzerling, they did a book on AP coverage of the Second World War in Germany.

What book are you working on?

I'm working on a second book about the collaboration between Anja and I.

Your favorite opinion, columnist?

I'm a big fan here in Pakistan of Zahid Hussain.

Your guilty media pleasure.

Facebook and stuff. Does that qualify?

Yeah, yeah, sure. That's media. Your favorite research tool.

Google. I just read a lot. Then, I find organizations that I really respect on something that I'm working on. And then I look at what they have, where they're coming from. And then I even get a hold of some of their people and talk to them. I really have a lot of respect for organizations that are on the ground. I want people on the ground. I'm not really a big follower of a lot of these think tanks.

Kandahar, Afghanistan

Words of wisdom for aspiring reporters?

Really challenge narratives. Look for narratives on the ground and really try to understand where you're coming from and how that influences how you question and how you frame your questions. Are you trying to really understand or are you trying to get them to say what you think? We confuse understanding with acceptance.

It's very important for young journalists to know is that our job really is to inform and to help people understand. Our job is not to cheerlead for the West, for democracy. Our job is to try to understand. When I did this honor killing story, I interviewed the brother who killed his sister. After I did the story, the editor, she said, “I sort of feel like we all have a little of that in us, you know, what will people say? Or are people laughing at me?” Of course it doesn't in any way justify, but it just helps you understand. So my advice is know what our job is and our job is to try to inform and to understand and to be able to question. We have to understand where we're coming from too. So, you know, we have to really be honest with our own biases and our own assumptions.

What's your number one don't do for aspiring reporters?

Don't judge.

Thank you so much Kathy Gannon for spending some time with us here. I really enjoyed this conversation and I’ve really valued your work for many years.

Thank you very much.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and brevity.

Share this post