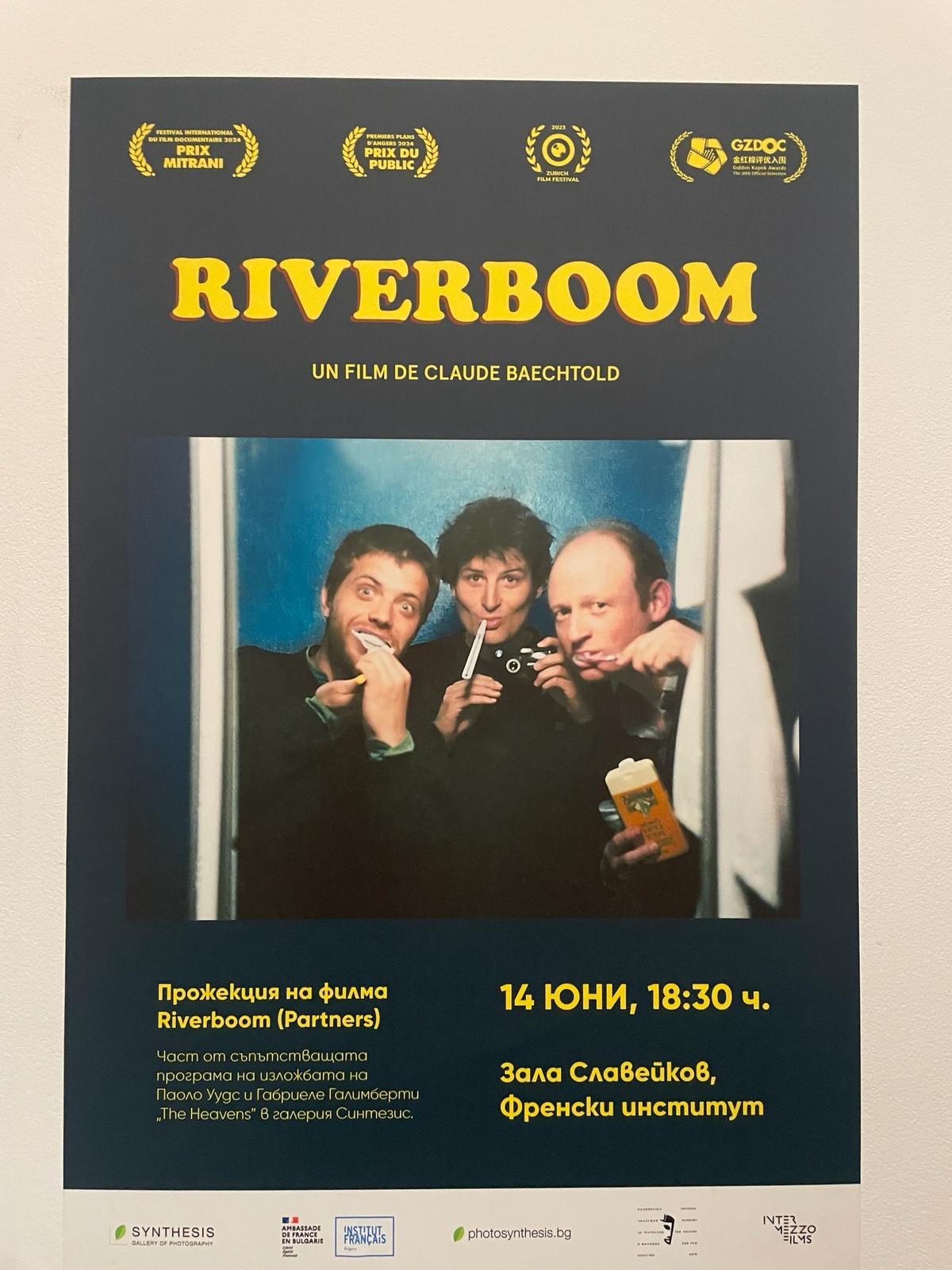

My guest today is Serge Michel, the chief editor and co-founder of the Geneva-based media outlet Heidi.news. Between 2011 and 2018, he worked for Le Monde in Paris, as deputy director and later founder and editor-in-chief of its African edition, Le Monde Afrique. He published his first reports in 1989 in the Journal de Genève. In 2001, he was awarded the Albert Londres prize for his reporting in Iran, where he spent four years as a correspondent for Le Figaro and Le Temps. In 2005, he founded the Bondy Blog in the volatile suburbs of Paris. Serge is the author of several books on Iran, China and Africa, Iraq and Afghanistan. He has contributed to publications such as Fortune, Foreign Policy and The Independent. In 2024, he appeared in the documentary film Riverboom, by Claude Baechtold, about a road trip he took in Afghanistan in 2002.

For this episode of The Reporters, Serge chose: “Le Renard et l'Oligarque” (The Fox and the Oligarch), his story about an epic battle between a Russian oligarch and a Swiss businessman over the “world’s best private art collection.”

Below are some highlights from our interview.

Serge Michel, welcome to The Reporters. It's great to have you here.

Thank you.

You picked a story for us called Le Renard et l'Oligarque, “The Fox and the Oligarch.” And it appears in the magazine, Heidi News. You are the editor in chief. I highly recommend people check it out. It's a Swiss publication.

I just saw you last week in Geneva and you were telling me that one of the reasons that Geneva is interesting is that roughly a third of the world's wealth is managed from there. It’s a place that is bound to generate interesting stories and conflicts and tension and drama. One different thing about this story is that it appears in essentially what is a small book. So it's different than your average news article. It reads essentially like a novel or maybe a treatment for a TV show. You get a lot more detail and rich storytelling than you would in your average article. Can you talk a little bit about why you like to tell these stories in a series in this format and what kinds of stories you look for and what do you get out of this format?

We created Heidi News in 2019. I was deeply frustrated by what you can read on an everyday basis. Of course, you have excellent pieces of journalism in many different outlets, but somehow it's kind of always lacking something. I thought, you have Netflix, the series on Netflix are tremendous. There is an art of storytelling, a link between each episode, and you see the characters evolve. This is often missing in news stories. You don't have the space to describe somebody, to go into his mind. Sometimes you have three words about someone. You don't really feel the person.

A hundred years ago, newspapers were full of what we call, in French, feuilletons.

They were like episodes of a story, sometimes fiction, sometimes nonfiction. The great reporters of the beginning of 20th century would go, I don't know, by boat to China, spend one month on the boat, spend two months in China, come back one month on the boat, and write a story that would be published day after day in the newspaper. And some of these stories would double the number of issues the paper was printing.

And I thought there is something to developing a story like this. When you get into an investigation like the one we did on Yves Bouvier and Dmitry Rybolovlev, “The Fox and the Oligarch,” it's a long story. You have a Swiss guy who inherited a furniture moving company from his father.

This is Yves Bouvier, who is the fox in this tale.

Exactly. And he has a modest origin story. He lives in Geneva. There's a lot of money around. So he thinks, how can I get rich? And then you have an oligarch straight from Siberia. Dmitry Rybolovlev has made a fortune in his lifetime. He was born in Russia and was the son of a doctor in the Soviet Union. They had some means but no fortune. He's a smart person, and manages well during the fall of the Soviet Union, privatizes a mine and other assets.

He makes a fortune estimated at $13 billion in a decade or so. He's one of the few oligarchs who managed to leave Russia with his money. He came to Geneva with his wife and doesn't know anything about Switzerland, about the way of life in the West. But he has a few ideas. He wants to build the world's most beautiful art collection.

“Bouvier would press Rybolovlev to buy a Rothko for, I don't know, $80 million, for example, whereas he himself had just bought it for $40 million.”

He had heard this was a way to be respected. It's a way to invest money wisely. And slowly, he will discover as well — he's divorcing from his wife — that somehow having money invested in very beautiful paintings, Picasso and others, doesn't take a lot of space, practically speaking. You can keep paintings in discrete places. Your fortune is secured.

In Geneva, there are not only banks and money managers and financial advisors and tax advisors. There is also something very special called Le Port-Franc (Free Port). It's a huge custom-free area which is highly secure and you can bring anything from anywhere in the world, have it stored with no customs oversight and then you can re-export it later. You pay the taxes only when you enter another country. It's like a wallet where you can put everything. And it's full of storage. So you rent a room there. You can have statues. You can have antiquities. You can have paintings. You can have a safe with banknotes inside. You can have anything you want. And you can even develop the room a bit. You can put in a nice carpet, some lights, and you can make it like a showroom.

It could be like an art gallery in a protected area where all your paintings are stored and you can show them to clients. They can visit your gallery and say, “Okay, I want this one, but I have a flat in Hong Kong. I want it in Hong Kong.” And then the painting will go to Hong Kong. The buyer will manage the taxes, the tariffs and everything in Hong Kong.

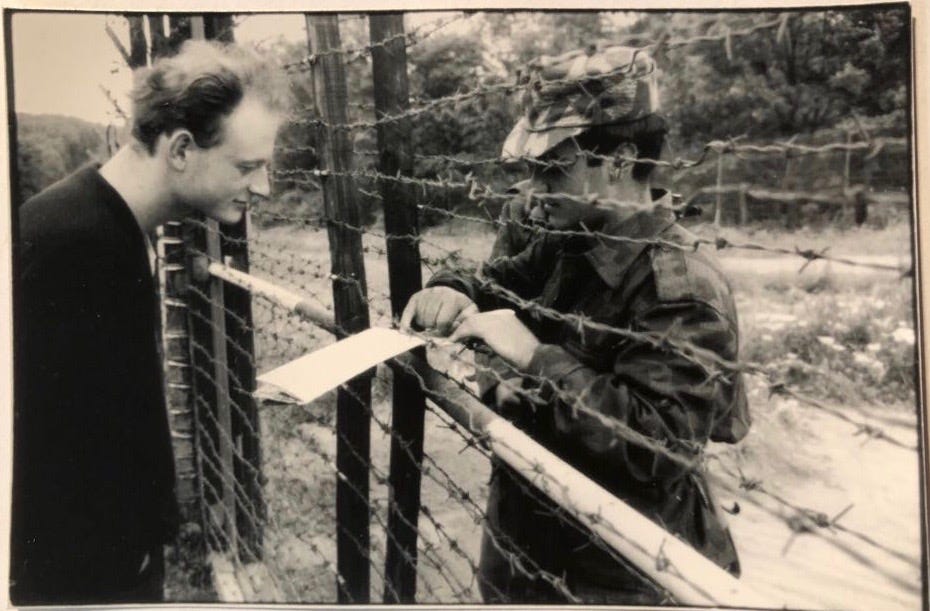

Serge (right) reporting from Afghanistan in 2002 with photographer Claude Baechtold (left) and photographer and director Paolo Woods (center)

Obviously the Port-Franc is used in the story for the purposes of moving paintings but I was also curious whether it is ever used for illicit activities like drugs? Do the Swiss authorities monitor it quite closely?

It's not a convenient place for drugs. It's convenient for objects. The illicit objects that have been sometimes found there were mostly smuggled antiquities. The Buddhas from Bamiyan in Afghanistan that were blown up by the Taliban were found in the Port-Franc in Geneva. Also Egyptian mummies and relics.

I told you about Yves Bouvier, the entrepreneur. He had a company that was moving furniture. One day, he thought: why don't I move more expensive things? If you move a painting or a statue or something very precious, you can ask for more money, it's less heavy, and you get in touch with interesting clients. The people who own an IKEA sofa are quite common; but the people who own a Picasso or a Rothko painting are interesting people.

“An oligarch is somebody that is very suspicious. Everybody who approaches an oligarch has dollars in their eyes.”

He opened a division in his company for moving art. It's amazing how many pieces of art need to be moved: a museum that is borrowing pieces from another museum for an exhibition; when somebody dies and people who inherit a fortune, with paintings and precious objects. There are many, many occasions to move precious goods. So Bouvier developed that. He rented more and more space in the Port-Franc because when you move these kind of things, you need a safe place. He was the largest tenant in the Port-Franc. He also invested in the company that owned the Port-Franc. It's kind of a semi-public company. The authorities in Geneva have a share. One day in the Port-Franc, he sees Dmitri Rybolovlev. Rybolovlev hadn’t been in Geneva for very long. He had a very nice villa in the Colony — this is the Beverly Hills of Geneva. It's a hill above the city where all the rich people live.

Rybolovlev said, “I want to buy the nicest paintings in the world.” Bouvier tells him, “You know, I'm moving them. I know who is selling, who is inheriting. I know the market from the inside so I can tell you, I have clues about what is on the market or what will be on the market before it reaches the market. And I can get you these things for the best price.” Rybolovlev is very interested. They agree on a 2% commission for Bouvier. Over the course of more than a decade, Bouvier will provide Rybolovlev with 38 beautiful pieces. It's actually one of the most beautiful art collections.

Bouvier will tell him: “This [painting] was 20 million, I absolutely have to pay 20 million, otherwise we'll miss the opportunity.” And Rybolovlev buys it for 20 million, and pays the 2% commission on 20 million. But actually, Bouvier, on many occasions, bought the piece before for 10 million. So he almost doubled the price of each piece that he provided to Rybolovlev.

So he was essentially working in the margins. He got 2 % of 20 million instead of 2 % of 10 million.

Exactly. And he got 10 million as a margin in his pocket. So altogether, he sold pieces of art worth $2 billion to Rybolovlev, but it only cost him $1 billion. Of course, it's not $1 billion of pure benefit. He also had to develop a large network to get these pieces. It's not easy to find a Picasso on the market. He had privileged relations with art sellers, gallery owners, and rich people with collections. It's costly to go back and forth to the owner of a Picasso and convince him to sell.

Still, quite often — you can see in the legal filings — Bouvier would press Rybolovlev to buy a Rothko for, I don't know, $80 million, for example, whereas he himself had just bought it for $40 million.

I'm not accurate because I don't have the text under my eyes. But it's an example.

Then one day in 2015, Rybolovlev got a hint from another art seller, probably a competitor of Bouvier, and he came to believe that he had been cheated.

You had an interesting quote from Bouvier early on in the piece where he makes the case that the value of any good, in this case a painting, is entirely dependent on how much the buyer thinks it's worth. If the buyer is prepared to pay 80 million because he thinks the painting is worth 80 million, then that's how much the painting is worth. Is that legally a defense that holds up in court or safeguards Bouvier against accusations of fraud?

In the end, the justice system couldn't decide whether this was a good defense or not. The relationship between the two — was it friendship? Was it a very close relationship? Bouvier got invited to birthday parties. An oligarch is somebody that is very suspicious. Everybody who approaches an oligarch has dollars in their eyes. Oligarchs tend to be reserved and live behind closed doors. But Bouvier managed to break into Rybolovlev’s inner circle using a lady that was kind of a guide.

She's a lady of Bulgarian origin, Madame Rappo. And when the Rybolovlev couple arrived in Geneva, they had no clue whatsoever. She took them around. She speaks their language. She introduced them to nice people. She was the first contact person they had in Geneva. Bouvier understood that this Madame Rappo was key to his project. He gave her a very high commission on each piece that Rybolovlev bought from him. Over the years, Madame Rappo got $100 million in commissions, which is huge. That was the price of her loyalty. She constantly told Rybolovlev that Bouvier was such a good guy, such a trustworthy person. And with her help, Bouvier managed to get into the inner circle.

“The challenge as a journalist is that the stories never end. The characters and the cases continue their life. It's very challenging to continue to follow a story. When do you stop?”

And then, of course, there was the divorce, which happens sometimes. Rybolovlev made his $13 billion fortune after he married her in the Soviet Union, in Russia, like 20 years before. So they had to share the money that was accumulated because they were together, they were married.

The husband tried to hide what he could from his wife to pay less for sharing. The wife hired detectives to learn how much her ex-husband owned.

Bouvier was so smart — his name is “the fox,” after all, in the story — he helped the husband hide money as a piece of art in the Port-Franc in Geneva. But also in other port francs. Because Bouvier had become the king of the port francs. He opened one in Singapore and one in Luxembourg. He had like three port francs. He moved the pieces from one to another.

So he helped the guy. But…he also helped the lady, telling her where the paintings were, how much they were valued. Everything. He played both sides.

In the first divorce judgment, Rybolovlev had to pay $4 billion to his wife. It was called the “divorce of the century.” Then there was another judgment that was never revealed, but it's more or less understood that she got another $1 billion. And Bouvier helped both and took many risks for both.

Then when Rybolovlev understood that he had been cheated, he asked Bouvier to come to Monaco where he had settled. He said, “Please come to discuss the last transaction we were speaking about.” Bouvier went there with his private jet and got arrested. It was a trap. At the hotel, there were men in black, and they arrested him. They took him to the police station, and they questioned him. And that was the beginning of the war between the two.

Serge on the cover of Migros Magazine, a Swiss publication

This is how you open the series — with this very evocative scene over the course of four or five pages where we follow Bouvier into this hotel and then the arrest takes place.

It's the beginning of the story. We started to work on it in 2019 and this trap took place in 2015. So we were four years late. There were many articles in the press about the case, like magazines, dossiers, and documentaries and things. There was a lot of stuff, but none of it got to the bottom. We took six months to gather all the possible documents from the lawyers of one side, the lawyers of the other side.

“When you make a fortune of $13 billion in 10 years in Siberia, there are probably a few things that you prefer not to be revealed.”

Bouvier had a good relationship with a private detective in Geneva. He basically told the detective, “Save me, please.”

The detective took it over and hired 25 lawyers around the world: Singapore, New York, Monaco, Paris, Geneva and Luxembourg. The detective took over Bouvier’s defense and sent people to Russia. When you make a fortune of $13 billion in 10 years in Siberia, there are probably a few things that you prefer not to be revealed. The detective managed to find some of these things, and have them published it in the Russian press, to dirty Rybolovlev’s reputation. It was la guerre totale.

Total war.

Yes. And of course, the other side also hired detectives. They even hired a former boss of the French secret services. The war lasted for five, six, seven years. And then there was this agreement, which is secret. Since then, the two parties, they don't speak anymore.

As a journalist, it's not only the story of a deal that went off the rails or the story of an oligarch being cheated or not cheated, it depends on the interpretation.

It's two worlds colliding: the nice, the modest, the trustworthy Swiss guy, the little guy. Bouvier is the guy you would like to have a beer with in a pub. And the oligarch who started from nowhere and ended up having private jets, private yachts, and one of the world's most beautiful art collections. It’s the collision between these two worlds.

We tried to go back to the childhood of each of them and understand who they were before meeting at the port franc.

There was a lot of material out there already when you started working on the story, newspaper articles, magazine articles, judicial files, and so forth. Then you began your own investigation. What were some of the key things that you learned that had not appeared in the press that surprised you?

I think before us, people had not understood the role of the detective in the story. Mario Brero is a very famous detective in Geneva. He was a key, and we got things about him, from him, etc.

And then one day, I heard the name of a lady. Somebody said, “There is this lady. She has something to say. She knows something…”

I wrote down her surname. Then I looked and found a business registration with her name. The address was Chemin de Chandelon. And in Geneva, Chandelon is famous because it's the name of the city’s prison.

I thought that was weird. And then when I put it on Google Maps, the red arrow pointed to the prison itself. So the lady was in prison! She had registered the company with the prison as the address. I wrote her a letter by hand and said, “We would like to speak with you. We heard you have something to say.” I sent it to the address of the prison. And then I received an answer.

“Bouvier used to organize sex parties, sex orgies to provide women for people from whom he would then extract information about a painting that was to be sold.”

She sent us a manuscript, the project for a book. And when we opened it, it was just amazing. She had the most incredible stories. A few weeks later, she came out of prison and we met with her. I work all the time with an investigative journalist that I adore. His name is Antoine Harari. So when she came out of prison he met her. [It turned out] that she had been one of the ladies that Yves Bouvier used to organize sex parties, sex orgies. It was a way for him not only to have relationships with women, but also to provide women for other people, people from whom he would then extract information about a painting that was to be sold. He needed information. I mean, to gather 38 such pieces, you need very good information. He built his information network by providing pleasure to his business partners.

Was he using the parties simply as a way to grease the wheels of conversation and make friends and get people talking or was he essentially kind of blackmailing them using their participation in these parties?

No. No blackmail. He had several flats in Paris, in the best neighborhoods of Paris. He organized parties there. Some of the guests had links to the art world. And there was a famous gallery owner whose name appeared in the Epstein files.

So this woman Sarah [from prison] appeared to have been used by Bouvier. We called her Sarah in the story. Bouvier used her to bring other girls and to organize things for him. When he was arrested, she was very angry with him. She had been left behind. She was in a bad situation. And she decided to take revenge.

She spoke to a newspaper in France, called Le Point. It's a weekly magazine. She described the sex orgies in Paris, with a famous call girl called Zahia that took part. And Zahia had attracted attention in France because she was a minor and she had sex with two very famous soccer players.

Le Point published Sarah’s story. Bouvier sued Le Point and won. He won the case because Sarah retracted her testimony after Bouvier took her to a hotel in Geneva and convinced her to retract her testimony.

“Bouvier sent Sarah to sleep with the suspected real father of that kid, and to extract DNA to prove that she was not his kid. That was the kind of mission that Sarah did for him. “

When Antoine, my reporter, my investigator, met Sarah, I told him, make sure that she doesn't retract again, and that if we publish anything, she will not retract. We managed to get elements that she couldn't take back, proving everything she said. It was amazing.

Basically, Bouvier took her back and convinced her to withdraw her testimony. He offered her a job. The job was to spy for him. So she became a spy. She started seducing people Bouvier wanted something from. For example, there was a lady, a lover of Bouvier. She had a daughter and she told Bouvier that he [Bouvier] was the father. Bouvier sent Sarah to sleep with the suspected real father of that kid, and to extract DNA to prove that she was not his child. That was the kind of mission that Sarah did for him.

Another mission was to go to the homes of enemies of Bouvier and take letters from the mailbox. She had a special little tool to open the mailbox and take letters out. She brought the letters to Bouvier and to the detective. She also took credit cards and went to ATMs and got about $50,000 using this system, with many different cards. One day she was caught when she was pulling a letter out of a mailbox. She could have escaped, but she didn't. She says she saw the light and wanted to be punished for what she did. She was sent to prison and spent two years there. The stories she told us were amazing and we managed to prove everything, to verify, to check that every single thing she said was true.

The film poster for Riverboom, a documentary starring Serge (right) about a road trip he took with Paolo and Claude through Afghanistan in 2002

Can you give me a couple of examples of how you went about verifying some of the things that she said?

She had documents. She recorded Bouvier, actually, without him knowing. She had screenshots of messages. She had email exchanges. Also, she recorded a long interview with him, a long discussion with him. Bouvier was suspected by the Swiss tax authorities to have evaded about 300 million [Swiss francs]. The Swiss tax office was investigating him.

But a tax investigator cannot conduct his investigation outside the borders of Switzerland. So, Bouvier thought that he would send Sarah to seduce the guy. He sent her to a tax conference in a nice hotel. She managed to hook the person. Then Bouvier told her to take him to Paris in one of his flats. And to make him have documents in his hand, like a pile of paper. [He said he would] take a picture and have cameras installed in the flat.

He said, [paraphrasing] “I will take pictures of the guy, like maybe half naked, with documents in his hand. And then I will manage to prove that he has investigated about me because this flat was mine, so he was in my place, with documents in his hands, investigating my case outside Switzerland, which is illegal. And that will cancel the whole investigation on me.”

Bouvier explains this very clearly to Sarah in a cafe in Geneva. And she recorded everything. Of course, Bouvier never confirmed this. But I mean, we know his voice, we know the way he speaks and it was clearly him on the recording. So that was quite new.

Earlier you said that one of the things you learned in the story was that it was about this clash of cultures, worlds colliding, essentially. On the one hand you have Bouvier, the nice Swiss guy who you can have a beer with. On the other, you have this rough and tumble Russian oligarch. But from what you've just described, it sounds like this nice Swiss guy essentially turned into a kind of international spy slash operator, somebody who was really doing all sorts of dirty tricks to protect his empire.

I would say just tricks. One of the issues when you do things like this is not to be accused of libel. We had to be very careful with the words we use. For example, we never said that Bouvier was a proxénète…

A pimp.

Yeah. But we said that one of his business partners was doing pimp-like activities. He was a guy who was recruiting girls, promising them careers on TV shows, like a singing academy on TV, things like that. But actually these girls were recruited in Annecy, near Geneva, in France, and were brought to Paris and participated in the parties, the orgies.

We said he had pimp-like activities and we were accused of libel, and sued, and we won the case in a court in Paris. We had to be very careful because Bouvier, with all his lawyers, would not forgive us a single mistake. That’s one of the challenges.

“This is the main quality of a journalist. You have to be curious. Curiosity is better than any university degree you might have.”

The other challenge as a journalist is that the stories never end. We all know that. An article, a picture, a documentary is like a moment, a photograph of something. And then life goes on. The characters and the cases continue their life. It's very challenging to continue to follow a story. When do you stop?

Now we understand a few more things about the case because we sold the rights for a TV series that's half American, half Danish.

One of the paintings that Bouvier provided to Rybolovlev is the famous Salvatore Mundi by Da Vinci. It's the most expensive painting ever sold. Christie's organized an auction in New York and it sold for $450 million. It's the most expensive painting ever sold. This painting was discovered somewhere in America by a secondhand shop. Someone bought it for a few hundred dollars then sold it to someone else for a few thousand dollars and so on. And then I think Bouvier bought it for 40 million and sold to Rybolovlev for 80 million and then Rybolovlev sold it, we think, to the crown prince of Saudi Arabia for 500 million. A single painting went from $1,000 to $500 million. And Bouvier and Rybolovlev were just part of the chain. So where do you stop your story? It's endless. That's probably one of challenges of our job as a journalist, as a storyteller — how to stop, to sleep.

I was going to say, how do I stop the podcast? I want to keep talking to you. Serge Michel, what an amazing story!

I do have one final question. You teach journalism. Can you tell me three key lessons that you teach your journalism students?

What a question. In English, do we say curiosity when you want to know something? This is the main quality of a journalist. You have to be curious. Curiosity is better than any university degree you might have. The second thing is energy. You need a lot of energy because nobody will give you this energy. When you're a journalist, it all depends on you. And the third is adventure. I think our job is an adventure. I would like to see that in young journalists. Our job of journalists has been so standardized. Some of journalism can be replaced by robots, by AI. But the real job should remain an adventure.

I encourage people to check this out and check out Heidi News. It's a really interesting publication. They have great art. The storytelling is terrific. Serge Michel, thank you so much for coming on and I look forward to seeing your next work.

Thank you.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Share this post