My guest this week is Joshua Hammer. Josh is the author of five previous works of non-fiction, including the 2016 NYT bestseller “The Bad Ass Librarians of Timbuktu.” A longtime Newsweek foreign correspondent, Hammer has written for The New Yorker, the New York Review of Books, the Smithsonian and several other publications. In the spring of 2025, Simon & Schuster will publish his next book, “The Mesopotamian Riddle.” For this inaugural episode of The Reporters, Josh chose a story he wrote for the New York Times Magazine in 2022: “He Was the Hero of ‘Hotel Rwanda.’ Now He’s Accused of Terrorism.” Below are some highlights from our interview.

Most of your journalism is narrative, and for those listeners who aren't familiar with that term, it’s a style of journalism that’s typically long and the storytelling unfolds much like a book.

The story you picked for us is a great example of the genre. “He Was the Hero of Hotel Rwanda. Now He's Accused of Terrorism” appeared in the New York Times Magazine on March 2, 2021.

Why did you choose this story for us?

As Sub-Saharan African bureau chief [for Newsweek] in the early- and mid-nineties, I covered the Rwandan genocide and civil war. And it was the most horrific and intense reporting experience that my colleagues and I ever had and the images and the stories that came out of that experience have stayed with me.

I'm still in touch with some of these people 30 years later partly because of this incredible bond that was formed by being there together. And so the story stayed with me and anything related to Rwanda I've watched.

Then this incredible tale broke of the arrest of a heroic figure who many Americans knew through the movie “Hotel Rwanda.” I could say for most Americans, their sole understanding of Rwanda, their awareness of Rwanda, came from this movie. And Paul Rusesabagina, the hero of the movie, was such an iconic figure.

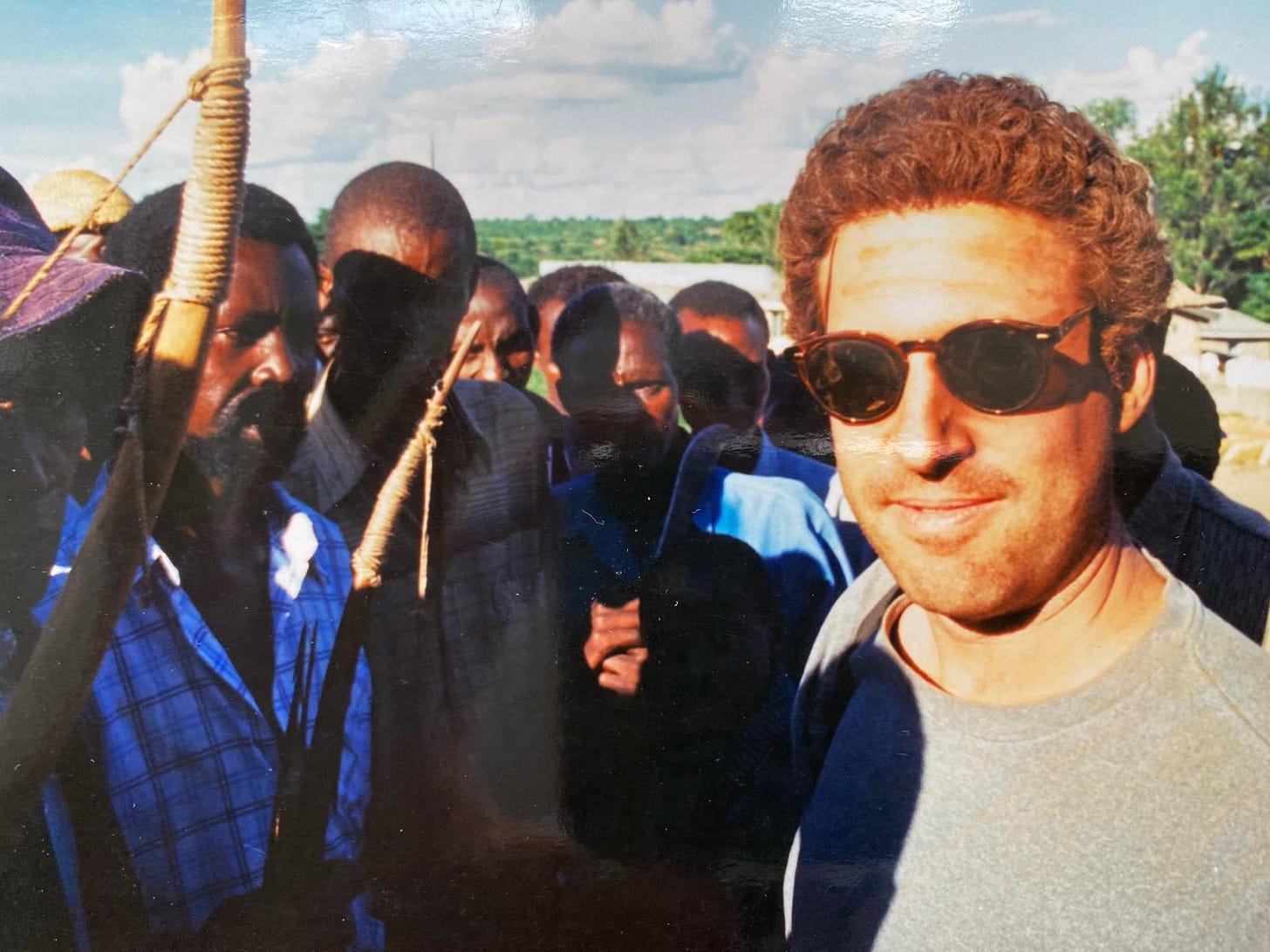

Joshua Hammer, south of Kigali, May 1994. Source: Scott Peterson

Could you take us back to those days as a reporter and tell us what it was like covering a genocide?

I was in South Africa at the time and I rushed back to Nairobi where I lived. We organized a small group of journalists there to travel in a Red Cross convoy from Bujumbura in Burundi, the neighboring country just south of Rwanda. We would travel overland into Rwanda as Red Cross workers.

We set out for Kigali, the capital. It was a full day’s drive. Everything was incredibly eerie and nobody was moving in any of these towns we passed through on the way up there.

It's like people were just locked indoors anticipating the worst. Not a soul in the streets anywhere. And then we finally reached Kigali and we began to see bodies in the river. And roadblocks manned by these killers, armed with clubs and machetes and we had to negotiate past them and just the images became more and more horrific as we got into the center of town and checked into [the Hôtel des] Mille Collines. That was the Hotel Rwanda.

So that's where we ended up. And, our little group of about eight journalists, basically landing in this place of refuge for Tutsis, who were terrified, and had made it to the hotel and were for the moment safe. I think there was a UN armored personnel carrier parked in front. That was apparently the only protection that these people had. There was a lot going on behind the scenes that we didn't know about, but that was the situation when we arrived.

This is really where Paul Rusesabagina’s story begins. [After the] genocide, Paul's story evolves in all kinds of strange ways, which we're going to explore. Paul Kagame takes power. But things get a lot more complicated. Now, you as a journalist have to sift through all these competing threads to try to figure out what's going on.

Yeah, so [Rusesabagina] emerges from this genocide as a hero. Kagame, I think, even recognizes his heroism.

I should also point out he was a half Hutu, half Tutsi. It was back in the days when those kinds of intermarriages took place on a regular basis. So he had been at ease in both worlds. But in the genocide’s aftermath, he seemed to shift more and more towards sympathy with Hutus and condemnation of Kagame. Again, some people said it was because he was competitive with him, aspired to become president himself.

Within a couple of years, he had left Rwanda and moved to Brussels, where there was an exile community that consisted of both Tutsis and Hutus.

But a lot of the Hutus who were in Brussels were these diehards who had fled the country after being involved in the killings. Some of them were just sympathizers with the genocidal regime. So there was a community of these people in Brussels. And Rusesabagina slowly, bit by bit, began kind of drifting into this group.

It's a little unclear what would cause him to make such a leap, but he did make the leap. These people began to sort of dominate his world. And gradually he transitioned from being an ally of Kagame to probably his most visible vocal critic.

And that put him on Kagame's radar screen as an enemy. And so the whole thing just kind of spiraled with Kagame considering him his main threat and Rusesabagina calling Kagame the devil incarnate. And as that rift grew, Rusesabagina then began to associate with a group that was planning an armed insurrection, sort of a quixotic attempt to overthrow the Kagame regime with these armed attacks from outside the country.

Members of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), south of Kigali, May 1994. Source: Joshua Hammer

And then at this point in the story, you drop this pretty stunning little twist in there, which is the theory of the double genocide.

Now, I don't think most people will be very familiar with this. I certainly wasn't and I also lived in Africa. So, tell us a little bit about this theory of the double genocide. What is it and why do you think it's taken hold?

In the aftermath of the genocide, the Rwandan Patriotic Front, Kagame's rebel group, took power.

A lot of these guys, their families had been murdered. Some of them, no question, were out for revenge. Kagame kept a pretty disciplined hold over the military, but there was no question that there were some rogue elements that went around and killed some Hutus. In some cases in large numbers.

It was nothing compared to the genocide. Journalists like me, who went into the country in the middle of the genocide, could see that every single church in the country was filled with corpses. There was no question that this huge killing campaign had gone on, and most of the Tutsis had been exterminated.

But the anti-Kagame, pro-Hutu forces began to try to craft this story that actually the real victims of this genocide were Hutus, that the story had been turned around somehow. Some Westerners traveled to Rwanda and wrote these purportedly investigative stories, books arguing that the Hutus were the real victims, claiming that these mass hidden extermination camps had sprung up Babi Yar style, hidden in the forests.

It was all nonsense. Nobody ever found evidence of this. Now, as I told you, you didn't have to look very far during the genocide of mid-94 to see thousands of corpses, the stench of death everywhere, interviewing the handful of survivors to know that the Tutsis had been exterminated.

There was no physical evidence of the other counter story. But nevertheless, this myth proliferated, propagated, and became an article of faith for a significant number of people, especially some of these Hutu extremists who were willing to do anything to bring down the Kagame regime.

It was sort of the classic alternate facts argument. And they had some Western allies who backed them on this, but none of it was ever verified. None of it could ever be verified because it was false.

President George W. Bush and Laura Bush meet with Paul Rusesabagina and his wife, Tatiana, in the Oval Office Thursday, Feb. 17, 2005. Source: Records of the White House Photo Office (George W. Bush Administration)

So I want to pause here for a second because some of our listeners are young journalists learning this craft and trying to figure out the basics of how to do journalism.

I'm curious if you could talk to us a little bit about what's involved in trying to get to the truth when you're dealing with competing narratives like this. You spoke about how there was no obvious evidence to support the [double genocide] theory. And yet there were people who were promoting this idea, pushing this theory, writing books trying to get this alternate theory on the agenda.

What do you as a journalist do when you're confronted with a fake news narrative or a competing narrative, and you have to somehow contend with it, even if on its face, it's obviously false.

First of all, you have to look at the question of evidence.

What evidence is there? What hard, on-the-ground evidence is there? And… I was there. Many journalists were there. We traveled with the Rwandan Patriotic Front through parts of the country that had just been liberated from the Hutus. You could walk into church after church, backyard after backyard, and count the bodies, see them all rotting in the sun. I mean, there were thousands of them. All you had to do was talk to people in these towns who had witnessed it. There were witnesses everywhere, so that was indisputable. On the other side, you had these people propagating this alternate story about what happened after the genocide. And there was no evidence.

I talked to a couple of UN investigators who admitted that there were some atrocities committed against Hutus. They had seen it but they were extremely measured and said absolutely without qualification there was nothing comparable to what happened to the Tutsis. And so that's pretty powerful evidence, people willing to say, “Yeah, there were some atrocities and even Rwandan officials were willing to admit that.”

South of Kigali, May 1994. Source: Scott Peterson

So you have to look at the credibility of the people. Now, some of the strongest advocates of this double genocide theory were people who were involved in the killings to begin with, who had ties to the people involved in the killings, or they were sort of marginal academics in the United States who had never even been to Rwanda.

It becomes this kind of circle of mythology that just gets kind of passed around and built up but where was the evidence?

So you look at the people who are spreading the stories, what their motivations were, you look at your own experiences, you look at the lack of evidence, and you have to put two and two together and realize that this was an attempt to twist the truth to serve their own ends.

Okay, so back back into the story. Now there's some indication that Paul Rusesabagina is, in the years after the genocide, beginning to align himself with these Hutu militias that are based in neighboring countries, Burundi and Congo, and starting perhaps even to supply them with material and moral support and logistics and things like that.

There's a pretty serious paper trail that shows Rusesabagina was actively involved in these groups that hit on him as a charismatic popular figure. They were delighted to have him on their side. So he began to actively raise money and handle logistics.

There's some evidence that he actually traveled to these areas personally to kind of rally the troops and was pretty heavily involved in all of this stuff.

So Kagame decided, “Well, it's time to get this guy.” There was some talk about killing him. They decided that that would not be wise so they concocted a fairly ingenious scheme to lure him in (which is where my story begins) under false pretenses into the country using an informant.

And it worked brilliantly, and they lured him to Kigali and immediately arrested him, and we know the rest of it, put him on trial. He was found guilty, sentenced to 20, 30 years in prison, and ultimately, after a huge amount of pressure, released after signing an apology for being involved in supporting rebel groups. And promising to stay out of meddling in Rwandan politics in the future.

And where is he now?

I believe he's home in Texas, keeping a very low profile.

So let's talk a little bit about what it was like reporting this out. You've been a war correspondent for many, many years. How did you learn to work in war zones?

Kind of picked it up as I went along, but really the trial by fire came in Somalia in ‘92 and ‘93. It was hell and it was terribly dangerous. You associate yourself with more experienced colleagues, right? Being around a couple of real hardcore war correspondents who had a decade or more experience and watching them work, you learn a lot. But when I got to Somalia, I did some really stupid things, I had no idea what I was doing.

I picked it up pretty quickly. By the time Rwanda came around a year later, I was pretty hardened. It had been quite a horrific experience in Somalia and you just learn a lot from being in a situation like that.

Tell me a little bit about the hurdles that you ran into when reporting this story.

The Rwandan regime runs a very tight ship. When you're there, you’re aware that people are often programmed to echo the party line, which can make it hard to get beyond surface-level statements. But knowing the country well, I could recognize when I was being influenced or used and still maintain an objective view. It was important to keep a clear head about figures like Kagame—not buying into the idea that he’s either a saintly figure or the reverse. The danger of falling into black-and-white arguments is intense in a place like Rwanda.

What was it like dealing with proponents of the double genocide theory?

They can be incredibly persuasive and talk your ear off with their theories, so you have to keep a very clear head. One notable figure was an American professor of African studies who had never been to Rwanda but was close to Rusesabagina, spreading this double genocide narrative. When I challenged him with Rusesabagina’s own statements, he was taken aback and couldn’t respond, which was telling. However, when my piece was up for publication, this professor went ballistic, bombarding editors with calls, posting online attacks on me, and accusing me of being brainwashed. Ultimately, his efforts had no effect, but it was an intense experience.

French officer conferring with a local Hutu official in western Rwanda, June 1994. Source: Joshua Hammer

What are some words of wisdom for aspiring reporters out there?

Don't focus so much on all the doomsayers about the death of journalism.

I think there's always going to be a hunger for it and a need for it. And if you're driven to practice this craft, just go ahead and do it. Find a way. Don't be discouraged about the rather dismal state of the journalism landscape.

What's your number one don't for aspiring reporters?

Don't take things at face value, no matter how persuasive the person delivering the story is. And don't look at things in terms of black and white, because stories are rarely black and white. In fact, they never are.

Your least favorite country to report from?

Iraq was definitely one of the worst, as you know, just a real hellhole that was thoroughly unpleasant to be in.

I concur heartily. Your favorite research tool, if you have one?

Well, favorite research destination is the British Library. Everything's there, everything in the world and it’s easy to find and easy to retrieve.

What about finding stories, while we're on the topic?

Well, now that I've moved more into books, the constant struggle to come up with ideas is a little less intense than it used to be, far less intense.

How did you do it in the old days?

Actually, a lot of it in those days was word of mouth, before the real proliferation of the internet in the last like 10 to 12 years. When I started out as a freelance writer in 2007, it was easier, I had a lot of contacts, I talked to a lot of people all over the world.

Stuff would come to me that wouldn't be necessarily out there all over the internet, you know? And a lot of those ideas would have been blasted out immediately now and the idea of exclusivity these days is almost impossible to have. But in those days it was possible to come across incredible tales that hadn't been discovered yet.

So now you have to find the tales that are already out there, but you have to come up with a unique spin on things to do it. It's harder, definitely a lot harder.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and brevity.

Share this post